In this week’s reading bundle, there was a piece titled ‘The Age of the Essay‘ by Paul Graham. It wove in and out through the history of the essay, how we write them, and why we write them. One thing that resonated with me was the difference of what we’re told an essay is in our early education days, and what an essay should actually be.

“In the things you write in school you are, in theory, merely explaining yourself to the reader. In a real essay you’re writing for yourself. You’re thinking out loud. An essay is something you write to try to figure something out.” – Paul Graham, Trying, ‘The Age of the Essay’

The ‘writing for yourself’ notion is what caught my eye as I was a student that heartily enjoyed writing essays, but that enjoyment didn’t arise until I found that my stride was only hit when the writing became for my own understanding. In the early days of being introduced to the very idea of essays, students such as myself were presented the iron-clad structure we were to follow to create a successful essay. Graham identifies them as the “topic sentence, introductory paragraph, supporting paragraphs, conclusion,” which is essentially the only way I was taught to write them.

Though, in the reading Graham is specifically referring to essays written about English Literature. This only resonated with me in terms of essays being written in English class, but the topics were broader. This was the single section in the reading that stood out to me as being dissociative in my experiences. Yet, in the rest of his analysis, especially in terms of being given a clear goal of what you’re writing towards, rang true.

Graham states that “the other big difference between a real essay and the things they make you write in school is that a real essay doesn’t take a position and then defend it.” For example I recall being given a prompt about a particular interpretation of a film we had watched, yet that wasn’t the interpretation I had gathered from my viewing. But the prompt was written in such a way that forced adherence by the students to argue for that interpretation.

Reading the above piece by Graham prompted me to think back to the essays I had to write in high school. The first touch I think I had with a differing essay was in Year 12 Media when our prompt was to choose a sub-genre of film that is alien to us and analyse it’s history. When questioned about what we’re supposed to be aiming for with the essay (whether it should be argumentative, expository, persuasive), my teacher just told us that we just need to explore the sub-genre and find what’s interesting about it to us. So essentially, in our Year 12 minds, we’re thinking this teacher is just lazily telling us that we need to teach ourselves about this sub-genre, then again my media teacher was always a bit kookier than the norm.

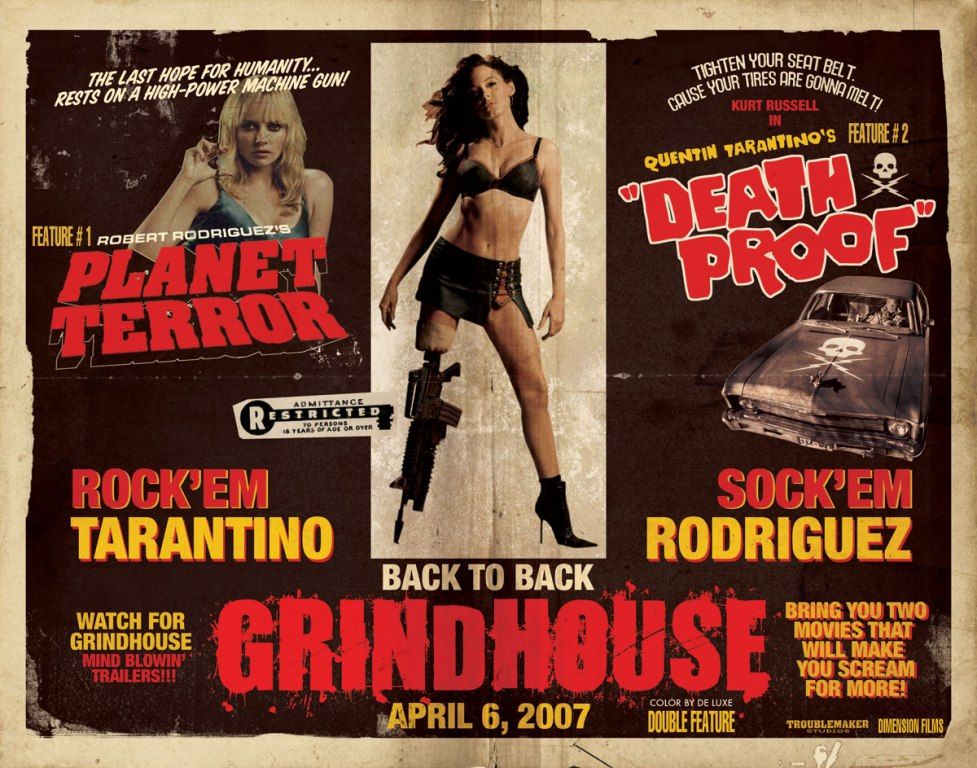

Anyway, I chose B-Movies because I had just become familiar with Quentin Tarantino and watched interviews with him where he’d consistently reference B-Movies. When I got to the end of the essay, I felt I had explained to myself what makes a B-Movie, in terms of tropes and the like, but also what makes people find genuine entertainment in B-Movies. My curiosity for what I shallowly self-classified as films that fell into the B-Movie genre allowed me to read into many different connections and reasons for why B-Movies are the way they are.

The films that first exposed the notion of a ‘B-Movie’ to me.

“So if you want to write essays, you need two ingredients: a few topics you’ve thought about a lot, and some ability to ferret out the unexpected.” – Paul Graham, Surprise, ‘The Age of the Essay’

The connection I’m trying to make with this memory and this reading is that Graham is correct in saying that “the best way to get information out of someone is to ask what surprised them.” I wasn’t expecting to find out what was appealing about that genre, I just set out to know more about it, which helped exponentially in rounding out an essay that was more surprising in nature than if I was just given a prompt to argue about that sub-genre.

Graham also touches on the importance of knowing your audience. Being aware that your writing will be read heightens your willingness to think deeper and accentuate your writing ability. Knowing that my essay was eventually going to be read by my teacher, who had made it well known to me that he’s well-versed in B-Movies, gave me added incentive to make sure the work I was churning out was well researched, as well as giving my own understanding of how I saw the genre from my perspective.

I guess I can see why we’re taught to write essays in high school with the intent of defending/arguing a point, as a kind of building block to improve the writing with the predisposed idea that someone will have to be influenced by it in some way. I just wish that Graham’s reading was something that was incorporated into the teachings as well, as a way to broaden the student’s horizon and to remove the daunting pressure when you were given a prompt.