Posted on May 2, 2019

Makeup Vloggers on Instagram

Networked Media 2019 Week 8

Who is the practitioner (what is their name?) and when were they practicing?

After realizing an emphasis on the beginnings of the DIY amateur video blogger, I was reminded of many online personas that I loved watching back in high school who had that particular style of grainy webcam quality video, framed poorly while they just rant and talk about whatever. Most of these personalities began on YouTube and have either worked on perfecting their craft and now product much higher quality content or have done the complete opposite of just disappearing off the face of the cyber universe. It’s either one or the other, I cannot think of anyone who has remained the same as they have started since the beginning of YouTube.

Now, on the topic of video practitioners on Instagram, I mentioned in class that I follow and consume a variety of videos on the platform, particularly two types: aesthetic videos, like cinemagraphs (looped, moving images), or quick snappy meme videos. In class, we also identified the popularity of make-up videos on Instagram, and although I do not follow and watch many of these types of videos, I suddenly remembered a very famous online beauty guru who blurs the lines of aesthetics and meme culture: Bretman Rock. He began his social media presence on YouTube in September 2012 while he was in eighth grade, and joined Instagram in January 2015, but only kept it private for his close friends and family. I cannot find the exact details of when he changed his Instagram setting to public, however, he has noted in an interview with Maria Sherman in 2017, that as soon as he made his presence public online, his “life did a whole 360”. Most of his content is fashion, make-up, and beauty related, but what makes Rock stand out from the abundance of online beauty gurus is his “ratchet” personality, which is one of the reasons why I watch his content more than others in the oversaturated industry.

Before Instagram, Rock was mostly on YouTube, Snapchat and Vine, and as discussed in class and from the readings, the journey of online video sharing from the ‘amateur’ to demands for high-quality production, and inevitable commercialization, this is all an important aspect in understanding networked media. Rock has expressed enjoyment for Snapchat and Vine but has understood the affordances of Instagram and has utilized it in his growing success as a young beauty influencer now with over 11 million followers (May, 2019).

With the photo or video you are examining, when was it produced (date)?

I have chosen to look at a series of videos Bretman Rock posted on Jun 10th, 2015 that showcase step-by-step tutorials on how to contour and highlight. I have only embedded part 2, as it was the video that had the least profanities and mature innuendoes.

View this post on InstagramHighlighting and contouring part 2 Mac Pro Longwear Foundation and Morphe 439 brush

How was the photo or video authored, published and distributed?

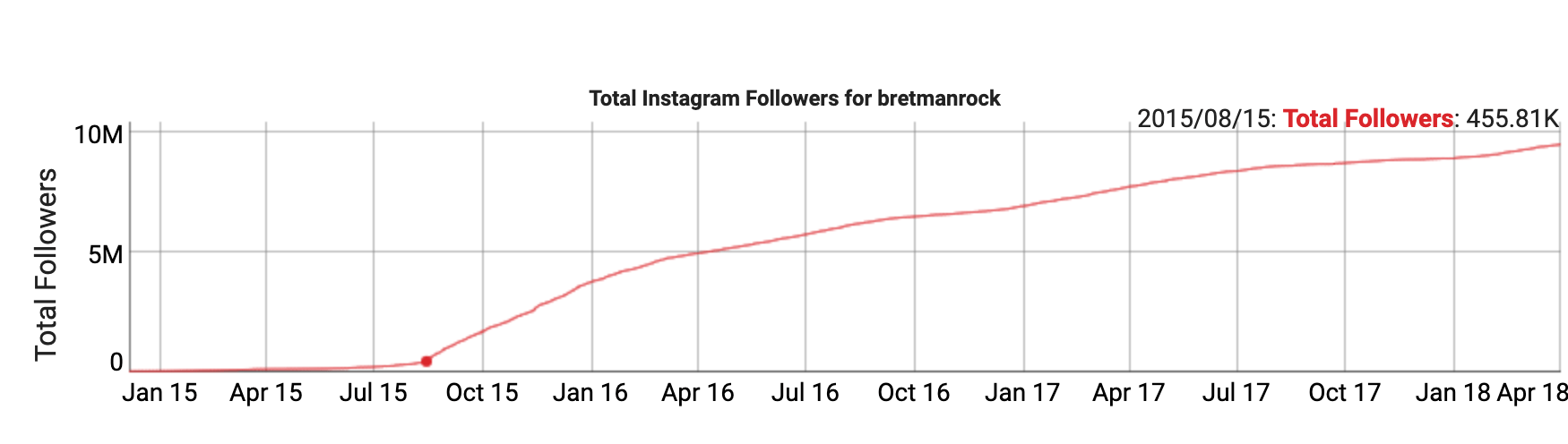

In an interview with Maria Sherman, Rock talks about how he would record a lot of these comedic short videos for his friends and family through Snapchat, but as Snapchat videos disappear in 24 hours, he decided to start uploading them on Instagram where they can remain more permanent. As Snapchat only allows for 10 seconds of recording, Rock’s tutorial is split up into 14 parts which didn’t face any issues on Instagram since the platform favors shorter videos. Furthermore, quick, snappy videos were trending from developing Vine culture, so the disjointed parts of the tutorial worked in Rock’s favor and granted him more viewing with each video. Taken from the SocialBlade statistics website, Rock’s Instagram boomed in August 2015, just after he posted the Contour tutorials, and so many consider these videos as his jumpstart to fame and recognition.

https://socialblade.com/instagram/user/bretmanrock

As our course work and readings have shifted from analog to digital media, I am noticing patterns of blurring lines between definitions of publishing and distribution of online works. Taking into account what Gerard Goggin observes in his chapter on ‘Mobile Video’, he notes that mobile media is ‘becoming highly integrated into the range of modes of consumption’, which is very evident with Bretman Rock’s involvement with online media. Back in 2015 when these platforms were still experimental and ‘amateur’, he seems to have been very fluid between each platform and thus, the publishing and distributing of his content merges and becomes almost one. Looking at publishing and distribution in the eyes of music, an artist can publish their music on their chosen platforms and receive revenue through said platforms, or they can go through a distribution company that receives a certain percentage of the revenue. And so, looking at how Rock’s tutorials have been posted on his Snapchat’s snapstory, then Instagram and Vine, and now downloaded and posted elsewhere on other Instagram accounts and YouTube channels, I would argue that Rock had published his videos through his own accounts on Snapchat, Instagram and Vine, while his fans downloaded and shared his videos across the cyberspace as an act of distribution.

References:

Goggin, G 2013 ‘Mobile Video: Spreading Stories with Mobile Media’, in The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media (eds.) Goggin G., Hjorth L., Routledge, New York, pp. 146-156.

Sherman, M. (2017). Beauty Vlogger Bretman Rock on How Contouring Made Him King and His Love for Frank Ocean. [online] PAPERMAG. Available at: http://www.papermag.com/beauty-vlogger-bretman-rock-on-contouring-social-stardom-and-his-love–2380005570.html

Posted on April 26, 2019

The Essence of a Film Festival + Fundraiser Preparations

Festival Experience Studio blog post #6

Before I address the updates for the fundraiser preparations, I briefly wish to discuss Robert Koehler’s article titled “Cinephilia and Film Festivals” as he raises issues of film festivals that I need to get off my chest. Prior to this studio, I had never attended a film festival, nor really knew much about what film festivals were like, let alone the vast types of festivals that happen all over the world. As my classmates and I pursue the creation of our own festival, what I observe from Cerise Howard and other guest speakers such as, Richard Sowada and Mia Falstein-Rush, is that they each have such passionate energy for film festivals which have definitely sparked a passion within myself and my other classmates. Thus, after reading what Robert Koehler has to say about film festivals nowadays having an aversion to cinephilia is truly heartbreaking. In particular, Koehler describes the Sundance Film Festival as “the horror show of cinema”, and declares that the festival neglects the indie films and the experimental, non-narrative films which is what ought to be celebrated at these festivals. Then, with a devastating revelation, Koehler accused Sundance of losing its loyalty to cinephilia and instead, deteriorate into a sort of market “allowing the free and rollicking exchange between buyers and sellers”. It is really, truly disheartening to learn about this, but this gives me all the more reason to work harder for MIYFF and push our beliefs in support of cinema lovers and the true essence of film festivals. Our film festival may be small, but if we remain true to creating an environment for like-minded film lovers to enjoy the films of today’s youth, I think this will be a step in the right direction, away from this “threat” to festivals as Koehler describes.

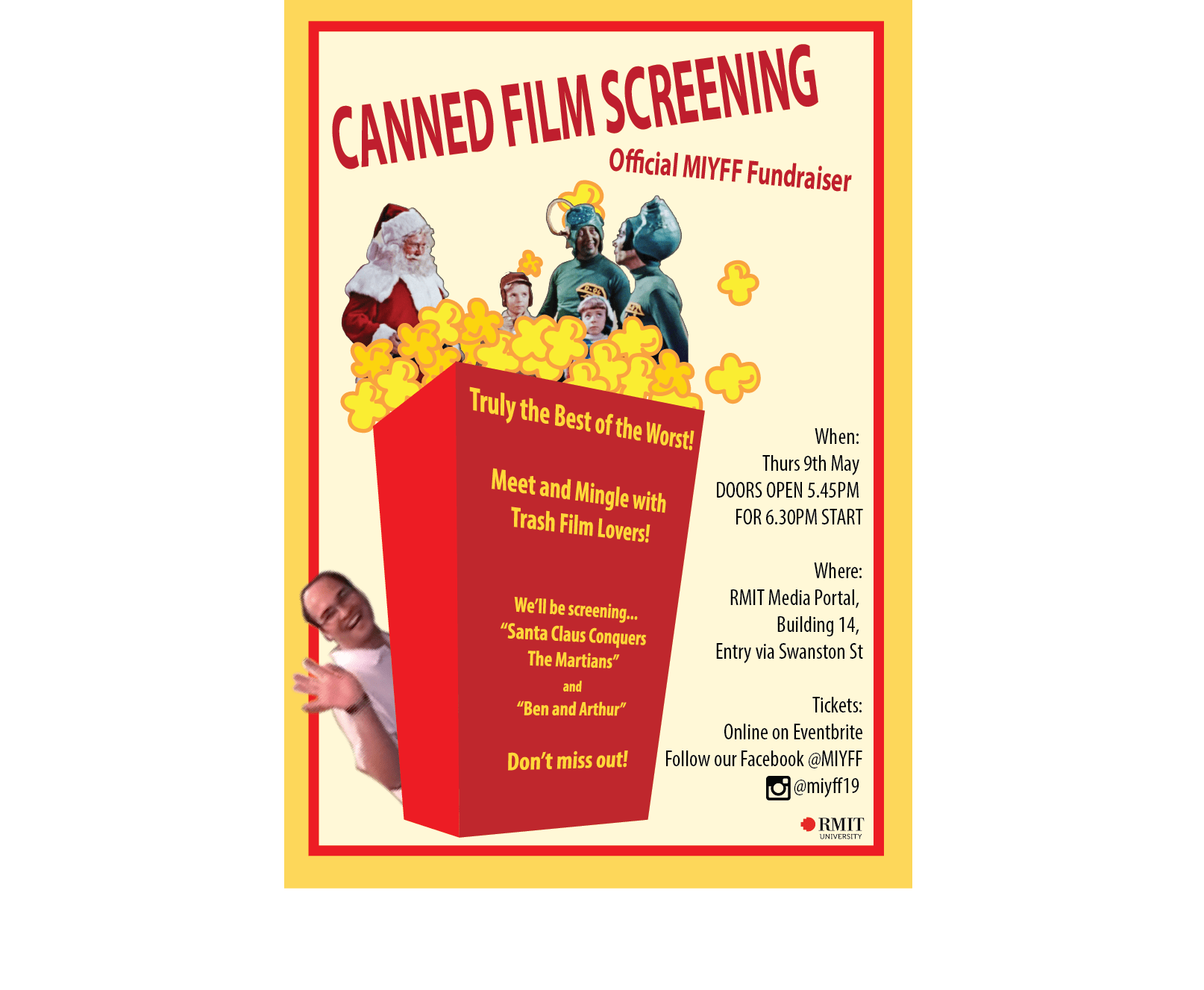

Quick update on how we’re going with the fundraiser, we have titled the event as “Canned Film Screening”, and we will be showing two films that are SO bad that it’s SO good, Ben and Arthur (Sam Mraovich, 2002) and Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (Nicholas Webster, 1964). I am a lot more comfortable with Adobe Illustrator, and I am quite proud of making my first poster for this fundraiser, utilizing bright colors and geometric shapes to create the recognizable popcorn box in hopes to easily communicate to viewers what the event is about: a fun film screening.

(20/05/2019: Updated and final version of the poster)

Posted on April 23, 2019

Aik Beng Chia

Networked Media 2019 Week 7

This week focuses on digital photography, in particular, “iPhoneographers” on Instagram. As a passionate digital photographer, many would assume that I should be in my element with this week’s topic because it must certainly be a subject that I can actively engage with. To an extent this is true, but to speak plainly, I had (emphasis on past tense) very mixed feelings about both the conversation on “iPhoneographers” and Instagram as a photo sharing platform, and these mixed feelings definitely leaned more towards the negatives. To sum up my thoughts briefly, I hope it’s understandable why someone like me, who has studied photography and gone through the journey of learning and developing my own craft (still developing and learning), would have a distaste for the term “iPhoneographer”, a connotation that somewhat invalidates the hard work of digital and analog photographers who spends time and effort to understand the mechanics of our cameras. And so, I do admit that I often find it insulting when someone with no background knowledge of photography will post a mediocre photograph with their iPhone with #beautifulsunset and #photographylife. However, as I have gone through the readings and continue to research into this bizarre world of iPhone photography, I have discovered that those who are successful in this field are nowhere close to the attitude of what I initially thought of iPhoneographers. The majority of these photographers have acknowledged the limitations of an iPhone, yet have developed ways to navigate around these limitations to still create such beautiful images. When these photographers explain that it is the necessity for the immediacy of publication that iPhones offer, then I have come to understand the appeal for iPhoneography and how this particular style has become so successful when done correctly. It takes me forever to get my photos off my camera and onto my Instagram, some reasons are due to anxiety with posting, but that spirals from the long, arduous process and uploading and editing which leads to more doubts about whether my photographs are worth posting. So, this week has definitely been very eye-opening to me and has definitely flipped my previously cold thoughts about iPhoneographers. In regards to analyzing a particular iPhoneographer, I have chosen Aik Beng Chia, a Singaporean artist who began working as a graphic designer, but discovered photography with his iPhone 2G in 2008 and has been shooting ever since.

What is the title of the photo you have chosen to analyze?

I have chosen to look at a series of photographs he posted on his Instagram that I believe are part of 香港 Zine, a magazine of photographs that he “made, lost and found” during his trip to Hong Kong in 2016. Chia has done so many projects and published/distributed them to many different platforms, there are photographs that appear on his Instagram, but not on his website, etc. etc. So, a lot of my answers to the following questions are more of a hypothesized assumption just by researching and trying to make connections with the sparse description attached to his photos and projects. However, in particular, for this blog post, I want to look at the post attached below.

EDIT: 05/05/2019

Aik Beng Chia has unfortunately deleted these photos off his Instagram, however from memory, there were black and white, beautifully composed photographs of people out on the street. Some were a low angle of a silhouetted man jumping over the camera, others were of beautiful Hong Kong architecture. I am still trying to find other sources of these photos so that I can link them to this blog post. Sorry for the inconvenience.

With the photo you are examining, when was it produced?

I believe that the photos were first published in his Hong Kong Zine in November 2016.

How was the photo authored, published and distributed?

I am unsure of exactly how the above photos were authored, but I specifically chose Aik Beng Chia as my practitioner to investigate this week because of his progress into becoming an iPhoneography. Hopefully, my research will summarise and indirectly answer this question anyway.

By trade, Aik Beng Chia is an illustrator and designer, and so, when he began exploring photography, he already had preexisting skills and understandings on how to frame and compose a photograph to a particular aesthetic. Chia had suffered depression in 2008 and in an attempt to find an alternative to medication in order to treat his depression, he found photography as a suitable distraction. Unfortunately, at the time, he could not afford a camera set so he resorted to just using the camera on his iPhone 2G, which now we can see as the beginning of amazing opportunities for Chia. He noticed many benefits of the iPhone camera in street photography, in that it was easy to carry around and secretly take photos of strangers, and later on in his career, he still enjoyed shooting with the iPhone because, with decent photo editing apps like Snapseed and the phone’s WIFI function, it meant that he could capture, edit and upload all on the same device. With the photos above, I can assume from his interviews, that he shot with either the Procamera app or Thirty Six, and edited with the popular app Snapseed. The reason why I chose the photos above in particular to analyze is because I was so surprised that they were #shotoniphone, but after researching and learning more about Chia’s background in design and the capabilities of these photo apps, I am very impressed and have found a new appreciation for what iPhoneopgraphy can offer. In regards to its publication and distribution, I found it very interesting that even though they were taken with an iPhone, it doesn’t look like they were published on Instagram, let alone online immediately at all. Instead, I believe that it was published in his Hong Kong Zine series, meaning he had spent time to edit and curate them with the other photos, which is contradictory to the general immediacy of iPhoneography publication. Regardless of timing, evidence of publication for the photos that I could find were in the Hong Kong Zine series, and online on his Instagram in 2019. I also could not find any evidence of these photos being distributed and published elsewhere, however, Chia has been very active in distributing his works to multiple magazines and news companies such as the Guardian, and the Instagram account @everydayasia.

References:

AikBeng Chia: Photographs. (2019). About Me. [online] Available at: https://www.aikbengchia.com/740625-about-me

Chia, A. (2015). Singapore through an Instagrammer’s eyes. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/gallery/2015/mar/17/singapore-through-an-instagrammers-eyes

Ciab, G. (2016). 香港 Zine by Aik Beng Chia – Invisible Photographer Asia (IPA). [online] Invisible Photographer Asia (IPA). Available at: http://invisiblephotographer.asia/2016/12/07/hkzine-aikbengchia/

Departure Mag. (2016). Coffee With Aik Beng Chia – Departure Mag. [online] Available at: https://departuremag.com/storytellers/coffee-photo-aik-beng-chia/

Kim, E. (n.d.). Photography is Democratic: Interview with Aik Beng Chia (ABC) From Singapore. [online] ERIC KIM. Available at: http://erickimphotography.com/blog/2013/07/03/photography-is-democratic-interview-with-aik-beng-chia-abc-from-singapore/

Nathan, L. (2015). Singapore photographer takes over Instagram account of UK newspaper. [online] The New Paper. Available at: https://www.tnp.sg/news/singapore-photographer-takes-over-instagram-account-uk-newspaper

Nookmag. (2015). Personalities: Aik Beng Chia. [online] Available at: https://www.nookmag.com/personalities-aik-beng-chia/

TAN, T. (2017). From illustrations to iPhone photography: Apple’s Red Dot Heroes to host workshops. [online] The Straits Times. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/tech/from-illustrations-to-iphone-photography-apples-red-dot-heroes-to-host-workshops

Posted on April 14, 2019

Good Morning, Mr Orwell! (1984)

Networked Media 2019 Week 6

Who is the practitioner and when were they practicing?

Deemed as the “father of video art,” Nam June Paik is a Korean American who reinvented the possibilities of video into an art form that aimed to spread global connectivity. Born in 1932, he began his works when he was 20 in 1952 and worked up to his final years till he passed away on January 26th, 2006 in Miami, United States.

What is the title of the video you have chosen to analyze?

I have decided to analyze Paik’s incredible television installation, “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell!” (1984), which is his response to George Orwell’s novel, 1984, which illustrates a pessimistic, dystopian world where television watches and controls its viewers. In contrast, Paik saw hope in the future of technology and sought to utilize video technology and his video art to connect people on a global scale.

With the video you are examining, when was it produced?

“Good Morning, Mr. Orwell!” was aired on Sunday, January 1, 1984.

How was the video authored?

The broadcast was a combination of live and taped segments, that was coordinated by Paik and hosted by George Plimpton, with the help of Executive Producer Carol Brandenburg, Producer Samuel J. Paul, and director Emile Ardolino. The one-hour long broadcast showcased many avant-garde artists, such as the musician John Cage, poetry by Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, as well as some live footage of Paris and New York. Furthermore, using the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer, that was created by Paik in collaboration with the television technician and specialist Shuya Abe, they were able to manipulate and alter the existing video images live that played true to the auteurship of Paik’s quirky style.

Due to its experimental nature, there were many technical difficulties causing glitches and delays throughout the broadcast in different countries which put some performers on the spot to improvise. Instead of seeing this as an unfortunate event, Paik celebrated these flaws and considered them apart of the “live-ness” of the broadcast.

How was the video published and distributed?

At first, I found it quite difficult to distinguish between the publishing and distributing of this particular piece of work because of its innovative digital sharing at a global scale. From what I understand of relating publishing vs. distribution to the music industry, publishing is what an artist puts out into the world, and distribution is the next step that takes the artist’s publication and shares it to other markets and viewers. Thus, bringing this concept to Paik’s “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell!” program, as the show was broadcasted in collaboration between New York’s station WNET/THIRTEEN and F.R. 3 in Paris and was transmitted at the same time to televisions in France, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands, and the United States reaching over 25 million viewers, the simultaneity of the broadcast is what makes me consider it as its first publication. Therefore, anytime after this broadcast that happened on the 1st of January, 1984, the program will have to be distributed to other spaces to be viewed. I could not find the exact method of how the program was delivered to different parties, but I have found information that the program has been edited into a 30-minute version that was displayed in many exhibitions including In Memoriam: Nam June Paik at the Museum of Modern Art.

References:

Marshall, C. (2016). Good Morning, Mr. Orwell: Nam June Paik’s Avant-Garde New Year’s Celebration with Laurie Anderson, John Cage, Peter Gabriel & More. [online] Open Culture. Available at: http://www.openculture.com/2016/09/good-morning-mr-orwell.html

The Art Story. (n.d.). Nam June Paik Artworks & Famous Art. [online] Available at: https://www.theartstory.org/artist-paik-nam-june-artworks.htm#pnt_4

Thomas, B. (2015). “Good Morning, Mr Orwell!”: Nam June Paik’s rebuttal to Orwell’s dystopian vision. [online] Nightflight.com. Available at: http://nightflight.com/revisiting-good-morning-mr-orwell-nam-june-paiks-rebuttal-to-orwells-dystopian-vision-on-the-first-day-of-1984/

Posted on April 13, 2019

Knowing our Audience + Meeting Mia Falstein-Rush

Festival Experience Studio blog post #5

What a treat it was to have Mia Falstein-Rush come down and speak to us. Currently working as a Programmer for the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), Falstein-Rush gave us incredibly insightful information about what it’s like working behind the scenes of film festivals, and what it’s like being a programmer for the biggest film festival in Melbourne. I found it particularly interesting about the flexibility one must have when working in this industry, and for Falstein-Rush who is such a hard-working individual, she expressed some really good advice on the power of volunteer work and exposing yourself to all types of work till you find a path to that goal or job you’ve always wanted. The nature of volunteer work has always been a tricky topic for me to grasp because growing up in a predominantly science and mathematical household, paid-work seemed to fit in a very black-and-white, concrete manner; just do the work and get paid by the hour. However, it seems that when it comes to the more creative industries, finding jobs through this trade requires fluidity and taking odd volunteer jobs here and there can make a huge impact on one’s career. Falstein-Rush has definitely opened my eyes to even more possibilities in my desired career field, and I will definitely keep a broader lookout for volunteer work that will be worth building experience for.

Other than working as a panelist and programmer, Falstein-Rush was also the Festival Director for the non-profit Seen & Heard Film Festival, a festival for advocating women filmmakers in the industry. The advice and materials Falstein-Rush fed us were absolute gold, and she definitely eased my anxieties regarding whether we really can manage to host MIYFF. She emphasized a lot on partnerships and the power of coverage one could make out of sponsors, to which she advised us on how we should write our sponsorship letters. She also made a good point that I will definitely apply to my own letter writing outside of the festival, which is the respect one should have for the other party that we are requesting favors from. Time is precious for everyone, and so to be respectful when asking for a favor, we need to keep our emails short and to the point, as to not waste their time reading pages of rambling, let alone if they read it at all.

Another point that Falstein-Rush discussed briefly that really resonated with me, is that as we embark on creating our festival and speaking to partners about our festival, we need to always keep in mind the purpose behind our festival. For her Seen & Heard Film Festival, she was driven to give a voice to women in the film industry and fuel the conversation of equality in these industry workplaces, and I really admire this genuine advocacy. So, with MIYFF, I reckon if we put genuine emphasis on supporting the youth filmmakers of today, our festival’s individuality and purpose will truly sing and reach the hearts of other passionate cinema lovers.

Posted on April 8, 2019

Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl”

Networked Media 2019 Week 5

Who is the practitioner (what is their name?) and when were they practicing?

Nick Ut began his photography career at The Associated Press (AP) in Vietnam in 1966 and covered most of the Vietnam War. He also worked in Tokyo, and in 1977, transferred to Los Angeles and still currently works as a photojournalist for the AP.

What is the title of the photo or video you have chosen to analyze (can you provide a link?)

I have chosen to look at Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” photograph from the Vietnam War (1955-1975).

With the photo or video you are examining when was it produced (date)?

“Napalm Girl” was produced on June 8th, 1972 during the Vietnam War.

How was the photo or video authored?

Kim Phuc Phan Thi, the memorable “Napalm Girl”, had been hiding in a Buddhist temple with her family before the Napalm bombs were dropped over her village. When the fighting had gotten closer to their whereabouts, the family decided to flee and run towards ARVN forces. However, unfortunately, a passing strike aircraft had mistaken these forces as NVA and dropped Napalm bombs over the ARVN, only just barely making contact with Kim Phuc. The Napalm had hit her back and left arm, and she tore off her burning clothes as she ran down the street till she reached a makeshift aid station where many photographers happened to be stationed at. Nick Ut was, of course, one of those photographers and he immediately captured a photo of her before she reached the station to be treated.

How was the photo or video published?

Nick Ut recounts in an interview with Michael Zhang in PetaPixel, that after developing the negatives of the film, many of his colleagues were confused about the image of a naked girl, and didn’t think it had a chance to be published. However, after Nick Ut explained to his editors and then to his boss the story behind the photo, they believed that the impact and power of the story overruled the rules of censorship, and immediately sent the image to New York to be published. I am unsure of which newspaper company were the first to publish nor can I find proof on how the photograph was sent from Vietnam to the United States. However, as these events transpired during the 1970s, it can be assumed that the image was sent through a photo transmitter, that scans the photograph one line at a time and then transmits the analog signal through a telephone line to whichever New York newspaper company.

How was the photo or video distributed?

I also could not find any verifiable evidence explaining exactly how the “Napalm Girl” photograph was distributed, however, I did find interesting articles discussing how the nature of its rapid distribution – as well as the development of broadcast television – heavily affected the outcome of the Vietnam War. Also titled the “first television war”, the Vietnam War was covered all across the news globally, especially in the United States. During this time, accessibility to multiple forms of media was a lot easier and convenient, in particular, television and photojournalism. With this evolution of media information, there were affordances for more media practitioners to be on the field of the war to capture and cover more scope of the devastation for the viewers outside of the war to observe. As quoted by Marvin Heiferman in her introduction on Photomediations, Joana Zylinska highlights the powerful nature of photography to engage with audiences on an emotional and intellectual level. Thus, with more eyes witnessing the horrors of the war, many people, especially citizens of the United States, realized that the war, including America’s attempts to aid in the war, was doing more harm than good. These powerful documentations were thankfully produced at a time where methods of distribution were quicker and more accessible between newspaper companies, broadcast stations, as well as for viewers on the streets at vendors, or at home with their own television set. Thus, the photograph of the “Napalm Girl”, as well as many other war photographs and televised footage, has been considered a key factor in bringing the Vietnam War to its end.

References:

Beaujon, A. (2014). Nick Ut’s ‘napalm girl’ photo was published 42 years ago. [online] Poynter. Available at: https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2014/nick-uts-napalm-girl-photo-was-published-42-years-ago/

Martinez, G. (2019). http://time.com. [online] Time. Available at: http://time.com/5527944/napalm-girl-dresden-peace-price-james-nachtwey/

Worldpressphoto.org. (n.d.). Nick Ut | World Press Photo. [online] Available at: https://www.worldpressphoto.org/person/detail/2094/nick-ut

Stockton, R. (2017). The Widely Misunderstood Story Behind The Iconic Image Of “Napalm Girl”. [online] All That’s Interesting. Available at: https://allthatsinteresting.com/napalm-girl

Time. (2016). The Story Behind the ‘Napalm Girl’ Photo Censored by Facebook. [online] Available at: http://time.com/4485344/napalm-girl-war-photo-facebook/

Posted on April 6, 2019

The Visuals of the Festival

Festival Experience Studio blog post #4

With our logo as the first design ever made and introduced to the team for the Melbourne International Youth Film Festival, my teammate Arnie and I had a lot of pressure to make this design because I believe that once the logo is created, the rest of the visuals of the festival are defined by this first logo. Thus, with this week focusing on creating the festival’s posters, I have been channeling my energy into working with my design team to create quality aesthetic content whilst also keeping in mind the advice from this week’s readings on how to effectively promote our festival.

To break down the design of the logo; the brackets and red dot before the title symbolizes the recording symbol that appears in the viewfinder of a camera when a user starts recording. We chose this illustration in particular because it’s an easily recognizable symbol for anyone who has used any type of recording camera, and it also suggests a “DIY” aspect that appeals to our demographic of young adult filmmakers. Furthermore, with the color palette of red, black and white, the colors resemble RMIT University which we believed to be a necessary connection to make as we are supported and based from RMIT. The “Y” in “MIYFF” in particular is highlighted red to really emphasize the youth aspect of the festival and is also connected to the “I” to accentuate that this film festival celebrates young filmmakers from all over the world.

Appropriately, this week’s reading was very suitable and helpful for us as we begin making the new promotional material for the festival. The chapter, ‘How to Successfully Promote Your Festival’ by Andrea Kuhn, discusses the importance of creating partnerships with other media influencers, and thus, the marketing team will be working on finding sponsorships for support with finances and media circulation for the festival, whilst the design team and I will work on creating these promotional materials, such as logos and banners for websites and emails, posters, and materials for our Instagram and Facebook pages.

Posted on March 31, 2019

Networked Media Assignment 1 – Annotated Bibliography

Name: Tessa-May Chung S3662677

I declare that in submitting all work for this assessment I have read, understood and agree to the content and expectations of the assessment declaration – https://www.rmit.edu.au/students/support-and-facilities/student-support/equitable-learning-services

Blog reflections

How do affordances of Instagram affect the way photos and videos are authored, published and distributed?

Annotated Bibliography

Hinton, S & Hjorth L 2013, Understanding Social Media. Sage Publications, London 2013. (pp. 21-31.)

Under a specific section in their book titled, “Using or Being Used?”, Sam Hinton and Larissa Hjorth unpack the media paradox of freedom and control; the conflict between a user’s ability to utilize the many possibilities of the web, and the control that is implemented by governments and administrative authorities. Hinton and Hjorth begin by prefacing the dotcom crash as “proof that the internet was resistant to control” which therefore supports Web 2.0’s quintessential evolution of introducing networking between users anywhere, and at any time. A particular example they give is the Arab Spring in the Middle East, to which utilizing the easy accessibility of the social media has given their small minority a voice, coverage, and support across the world. With an increase in smaller voices finding ways to be heard amongst the competition with larger entities through social media, the governments in some countries sought to understand and engage more effectively with their citizens by paying more attention to this analytics. Therefore, as the number of users begins to increase in their freedom of speech via social media, government monitoring, and data collection also increase, thus a new form of control in the world of New Media is introduced.

Hinton and Hjorth mention Wendy Chun’s contention that it is “the interests of the companies behind these services to foster and develop the illusion of control” (2006), to which this new form of control is not so obvious to the mass users of social media. They explain that while users are given freedom and empowerment by using social media for their benefits, they are also “subject to the control mechanisms of the information society”. The information of users is analyzed and sold so that companies can match ideal products and services through subliminal advertisements to entice users to purchase these goods. Thus, users are given the illusion that services are free for their enjoyment when ultimately, they are being controlled in a much more subtle and calculative way. In regard to Instagram as a popular social media platform, many do not identify this perceived affordance that in lieu of paying for their services, their information is being analyzed and sold to external companies. Although feeling empowered by the capabilities of posting and sharing what users feel that they have authored themselves, there is that “illusion of control” where every action and information of the user is being monitored and managed. As a specific example on Instagram, users are free to choose and select the profiles they follow and have the freedom to like and share whatever to whomever. However, despite feeling empowered with this freedom, their actions are also being analyzed, to which specifically tailored advertisements and perhaps other sponsored profiles are placed in their newsfeed to entice these users. Thus, for a newsfeed that began as a making of the users’ own free will and choice, has implicitly shifted into a corporately controlled collection for the company’s benefit as well.

Ultimately, Hinton and Hjorth do not conclude with a solution for this contradiction of user empowerment with the implicit user information control. However, they also express that “if you want freedom, then you have to submit to control”, suggesting that the dichotomy of freedom and control co-exist in a paradox that will co-evolve with the New Media’s own developing nature.

Niederer, S 2018, Networked images: visual methodologies for the digital age. Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam. (pp.1-26)

In this article, Dr. Sabine Niederer discusses her research and findings on the evolution of visual platforms on the web, and its relationship with the users as a growing network. She describes the notion of a ‘pictorial turn’ as “a practice driven by users and facilitated by platforms, in which more and more users increasingly share visual content and engage with it.” Hence, the nature of online networking is less of a literal displacement from text to image, and more of an understanding of how users engage with online platforms and its ability to allow a network of authoring, publishing and distributing visual content. This concept becomes the central idea of her studies and arguments as she further discusses the vernaculars of a platform; the distinct “visual language” of each media platform. In 2017, she conducted a subproject looking at the particular visual vernaculars of different social media platforms in regard to the discourse of climate change. Specifically, she looked at Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Twitter, Tumblr and Google Images and was able to highlight the key differences that distinguish each platform from each other, thus noting the affordances and constraints of each platform that determines the nature of how users author, publish and distribute the content.

Particularly looking at her findings for Instagram, she identifies that the platform prioritizes the image aesthetics and that the most engaged – the most popular and trending images – happened to have a total absence of text. In relation to the course prompt, the affordances of Instagram recognized in this study by Niederer can be seen as the visual aesthetics of its layout. Therefore, it can be identified that users who author and publish “beautifully edited” pictures, as opposed to someone who puts more emphasis on text rather than the image aesthetics, receive more recognition and distribution by utilizing Instagram’s affordance of the layout. In comparison to the platform vernaculars of Facebook, Niederer recognizes the emphasis on text-based posts, thus Facebook users aim for “shareable statements” that are mostly non-controversial with large fonts so that other users are more likely to validate the post and feel encouraged to share. Parallel to Instagram, the lack of priority for text may seem like a constraint, but Niederer suggests that the limitations of a platform are what conforms the mappings for the user interface. Thus, in Instagram’s case, users are encouraged to author, publish and distribute aesthetic and visually engaging images due to the platform’s layout that brings more attention to the image rather than to text. Niederer, therefore, concludes with the emphasis of understanding the relationship of the platform vernaculars’ affordances and its relationship with its limitations, which ultimate defines the nature of how users engage and interact with social media platforms.

O’Reilly, T 2005, ‘What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software’, viewed 1 March 2018, O’Reilly Media Inc., https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

This article, written by Tim O’Reilly, elaborates on the fundamental changes and opportunities that the new era of Web 2.0 has created for media and its users. Upon illustrating the nature of Web 1.0 as a single connection between a user and a platform, Web 2.0 is described as the new “power of the web to harness collective intelligence.” Thus, the key point O’Reilly centralises about Web 2.0 is the new opportunities for collective networking.

More specifically, O’Reilly expresses, in regard to the image sharing platform Flickr, that the concept of the categorisation of images is called “folksonomy”, which is defined as the categorising process done collaboratively by using specific keywords; a concept now familiarly known as “tagging”. O’Reilly further discusses the creation of RSS, a program that encapsulates the essence of Web 2.0 by bringing together information and sharing from all over the web. Instead of a user having to manually check for updates on multiple websites, the RSS feed acts as a central figure connecting the user with all their desired websites, allowing users to customise whom they are “subscribed” to and therefore provide notifications whenever there are updates. O’Reilly emphasises how this evolution of the web allows for peer-to-peer interaction, “they can see when anyone else links to their pages, and can respond, either with reciprocal links, or by adding comments,” and although this article was written before the creation of Instagram, one can clearly see how social media platforms today are born from this concept of collaborative integration. Hence, applying these concepts to Instagram, one can deduce that a fundamental reason to Instagram’s success in this new media era is due to its convenient accessibility for users to connect with one another, as well as the ability for the platform to connect with other social media sites. As mentioned previously about the concept of “tagging”, which allows for an overlapping of images and information rather than rigidly structured categories, Instagram implements the use of “hashtags” where users can identify the themes and subjects of discussion of their post, which consequently spreads coverage for their images. A recent example of this is a post by the Fitzroy café and culinary store, CIBI, utilizing hashtags and other tagging hyperlinks with the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival. This concept is the evolution of the RSS that O’Reilly highlights, demonstrating the fast-paced capabilities of hyperlinking that is beneficial for both parties in terms of coverage, support, and networking.

This nature of hyperlinking from an individual entity to another is the essence of what O’Reilly contends in his article; this new age of a “collective intelligence” where minds and crowds are intricately connected through the internet and media. This article is limiting in discussion for the course prompt as it was written 5 years before the creation of Instagram, however, despite its out-of-date perception of New Media, the article still provides an in-depth description and analysis of the beginning of Web 2.0 and the fundamental tools it has provided for the expanding evolution of New Media.

Posted on March 30, 2019

Alone we can do so little, together we can do so much

Festival Experience Studio blog post #3

So far one month into planning and to be perfectly candid, it is very overwhelming. Looking around the classroom, I reckon the general vibe is the discomfort of paddling in deep unknown waters, especially since most of us have never organized a public event, let alone to this extent.

But…

With our first assignment done and dusted, we are all now shifting our attention to the fundraiser, and of course, the final film festival; the organization, marketing, and for me in particular, the design and marketing materials. My strengths lie in the production side of event organization, and so with these film festival events, I will be focusing my energy on directing and filming the trailers, creating posters, and designing posts for our social media accounts, especially Facebook and Instagram. Our class seems to have split into two general groups; one for programming and public relations, and the other for anything production related. In this group, I hesitate to take the lead, but with classes feeling directionless at times, I want to achieve a balanced, collaborative atmosphere with my team whilst also making sure we remain productive and churn out materials for our public relations team.

“Production is like design— ideally it combines form and function. Some of its tasks intersect with other departments, such as the technical coordinator or the PR and graphic design people.”

Taken from Andrea Kuhn, “Who Is Organising It? Importance of Production and Team Members (Links to an external site.)” in Setting Up a Human Rights Film Festival, vol. 2, Human Rights Film Network, Prague, 2015, pp. 71

From this week’s reading, I really resonated with the discussion regarding design work and the necessity of integrating departments. Work within the creative media industry cannot function without group work, and as my classmates and I endeavor to run a live film festival, it is paramount that we work together in a fluid environment. By “fluid”, I mean that whilst we may have departments with specific roles, tasks should bleed between departments just as described in the quote above. I know from experience that creative media projects like this cannot work with segregated departments, but also cannot function if everyone doesn’t have a role. So, now with roles finally established, my game plan for the upcoming weeks is to keep open communications between my design team with the marketing and coordination team to make sure we’re all on the same page to produce quality content.

Posted on March 27, 2019

The Paradox of Freedom and Control

Networked Media Week 4

This week is all about New Media and Social Media, and the best way that has been described to me is the imagery of a plant in a jar of water. The other tutor for the course, Elaine, described New Media being the jar, and the roots as social media, a growing organism contained within New Media. As the jar grows bigger, so will the roots, thus suggesting that as New Media expands and evolves, naturally so will social media. So, after a week of studying the nature of affordances and constraints in the design of everyday objects and tools, specifically applying these thought processes to our understanding of New Media has raised many questions that I have about the dichotomy of freedom and control for online users.

So, backtracking a little… have a look at another amazing post I found on r/crappydesigns:

Maintenance put new locks and handles on the gates for security from CrappyDesign

The video shows a security door that is locked by a pin code to prevent unauthorized clientele from accessing the ground (a constraint). However, the person recording the video has clearly identified an affordance of the flawed design, that allows them to manipulate the inside handle from the outside, allowing them, or anyone else, the ability to access the restricted area. Alluding back to a reading from last week, the idea of “perceived affordances vs. real affordances” has been argued that a skilled designer will be able to take in all the affordances of a design and use it effectively, rather than just looking at the object with only the affordances it was expected to accomplish. However, besides just wanting a designer to embrace all the designs’ affordances, when looking at New Media, I believe that it is essential for designers, programmers, and engineers to understand all the real affordances of their design for a means of safety.

Looking at the 2016 release of information about Gmail users, they had calculated that there were more than 1 billion users, clearly a popular email platform because of it’s free accessibility and easy navigations that make it easy people to use. However according to Trend Micro, terrorists had also gravitated towards this platform, and it had been estimated that 34% of these 1 billion users were in fact jihadists. Fortunately, the FBI have been able to track down these users by navigating their IP address. But, this doesn’t just stop at Gmail. Other smaller emailing platforms such as Mail2Tor and SIGAINT are also being used by jihadists as means for communication, however these platforms make it a lot more difficult for law enforcement to track down their IP addresses. The platforms work with a system that encrypts and bounces signals across the globe, thus throwing law enforcement off their scent. In particular, according to a study by Trend Micro, Telegram became a very popular chatting service for jihadists because of its encrypted and anonymous affordances. This service was created by a Russian Tech Entrepreneur who was an advocate for privacy and freedom online, but then that raises the question of what are the costs when there’s too much freedom in the world of New Media?

In the reading by Sam Hinton and Larissa Hjorth, “Understanding Social Media”, they address Wendy Chun’s understanding of the dichotomy of control and freedom as a paradox. They state that “if you want freedom, then you have to submit to control”, which is a battling opinion that I’m sure many online users have conflicting thoughts about. The world of New Media promises so many possibilities for users, like how the very concept of cyberspace is timeless and infinite. So why the hell should we be put under constraints that limit us from exploring this infinite universe? I’m sure that these were the very thoughts of the creator of Telegram, and of course, he did not intend for their platform to be used by terrorists, but unfortunately… they did. And so, control had to be implemented despite the platform’s promise for privacy and freedom.

Thus, this paradox of freedom and control hangs over our heads, with an infinite world of incredible possibilities at our fingertips, but also dangers that lurk just as close.