When you take public transport to and from university, it’s impossible not to notice the amount of people looking at their mobile phones. Whether they’re listening to music, scrolling through social media or taking a call, it certainly makes you wonder what commuters used to do on public transport as little as fifteen years ago.

On my way home from uni on Tuesday night, I happened to be standing behind a young woman – probably about my age – who, like so many of those around her, was using her phone. Glancing at her screen, I noticed that she was flicking through an extensive catalogue of photos. Considering that our reading from Susan Sontag this week was entitled On Photography, I took the opportunity to look at some of these now everyday objects in more detail.

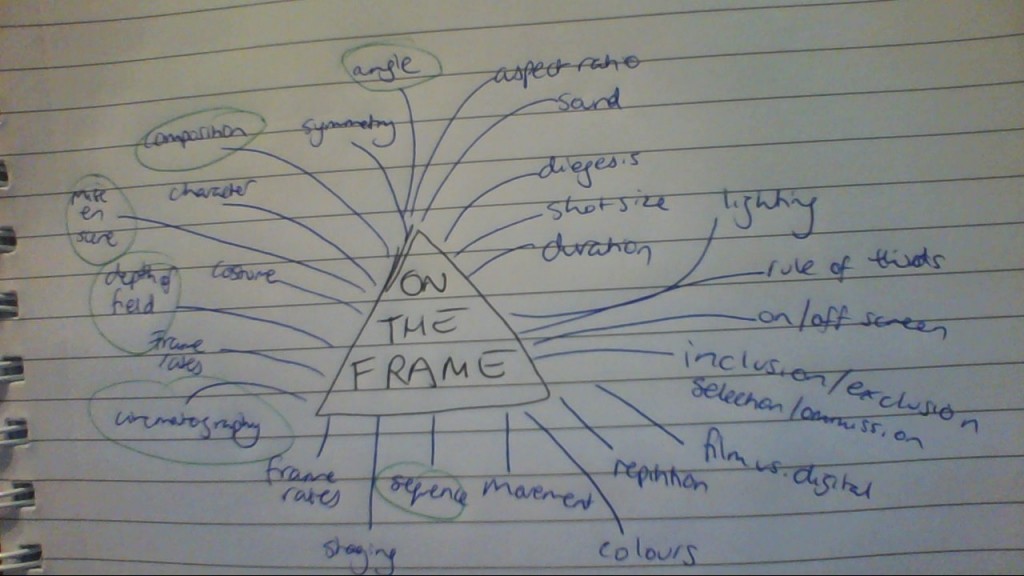

The first thing I noticed was that it was not immediately obvious where these photos were coming from. Rather than appearing on a Facebook or Instagram feed, they took up the whole of the mobile’s screen – leading me to remember last week’s discussion of the importance of a physical frame or lack thereof.

The sequence of the pictures also interested me. The pictures seemed to come in groups, but I couldn’t find any tangential connections from one group to another. Some of the pictures were quite beautiful, reminding me of Sontag’s assertion that photography is becoming like dance and sex in the sense that is a commonplace art form that is not frequently recognised as art. Some of the pictures I assumed were taken by professional photographers, and therefore were likely to have been made with art in mind. However, even some of the pictures that were clearly taken by amateurs for other purposes – holiday snaps to share with friends, selfies to show off a new look – had an artistic quality that couldn’t be denied.

Fashion pictures turned to cartoons turned to screenshots and then came the photos that interested me the most: two or three close-up pictures of some shaky letters scratched into a human wrist. It was obvious for many reasons that this was no stylised professional shot; this was a self-taken photograph of somebody’s (successful) attempt at self-harm.

The woman in question seemed not to be fazed by these pictures that certainly shocked me, and I can’t judge her for that as I have no idea of the context. Perhaps this was a retrospective picture from a friend celebrating a year’s recovery from depression, or my judgement was really off and it was somehow faked. However I must admit finding it an unpleasant surprise how, with only a slight, half-second squint, the woman swiped away the picture as she had the Spongebob cartoon and shots from the latest fashion week.

It brought me back to what I found the most interesting part of Sontag’s reading, which was her discussion of the ethics of photography. She writes:

“Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention. Part of the horror of such memorable coups of contemporary photojournalism as the pictures of a Vietnamese bonze reaching for the gasoline can, of a Bengali guerrilla in the act of bayoneting a trussed-up collaborator, comes from the awareness of how plausible it has become, in situations where the photographer has the choice between a photograph and a life, to choose the photograph.” (Sontag, Susan; On Photography; 1973; Penguin (Harmondsworth); p.11-12)

I found this statement to be particularly interesting as although it was written in 1973, I feel it is particularly relevant in this age of citizen journalism. Often I have seen footage on the news of a vicious beating or racial attack, and have wondered why the person behind the camera was not offering to help. As Sontag suggests, there seems to be an ever more popular view that is is acceptable to photograph rather than intervene (the two actions being mutually exclusive in her opinion).

However, in the case of the picture I saw on the tram, we have to look at the ethics a little differently, as the same person taking that picture was the victim. Firstly, I think this brings up the interesting idea of the ‘social media generation’; are we so public with our lives, so constant in our broadcasting of our own cultivated images that we now even post selfies of our attempts at self-harm? Perhaps this is an argument in favour of social media, that we can be open and share our pain, but that depends on the reaction of the viewer.

This brings me to the other side of photography ethics that Sontag refers to: the ethics of the viewer. Sontag writes of the way viewers are distanced from the events of a photograph, suggesting that, “A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it . . . most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter.” (Sontag, Susan; On Photography; 1973; Penguin (Harmondsworth); p.9-10) While Sontag here talks about tourists using photography to make the unfamiliar familiar, I think that her statement can also apply to the desensitisation we have to what we see in photographs. Despite the perception we have that photos are concrete evidence of real events (another of Sontag’s points), the one-dimensional, neat encapsulation of a moment distances us from it’s true consequences.

In constantly seeking to ‘frame’ the world, are we costing ourselves the opportunity to react to real life events both as the photographer and the viewer?