Who is the practitioner (what is their name?) and when were they practicing?

Nam June Paik, sometimes referred to as the “father of video art”, was a Korean American artist that was active from the early 60s right up until the 1990s.

What is the title of the photo or video you have chosen to analyse (can you provide a link?)

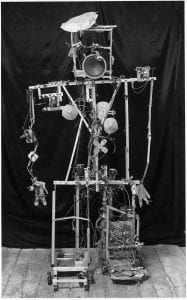

The piece I have chosen is Nam June Paik’s first robot, K-456. It is named after the Kochel listing catalogue number of Mozart’s concerto N. 18 in B-flat major. It can be seen here.

With the photo or video, you are examining when was it produced (date)?

It was made by Paik in 1964, this was very early in Paik’s foray into modern art, and was his first attempt at automated robot.

How was the photo or video authored?

The concept of the robot came from Paik wanting to create a robot for impromptu street performances that create a “sudden show” or “split-second surprise”. To create K-456, Paik used a selection of metals, cloth, speakers and wheels that he scavenged from various sources. This reflected what would become a staple of his artwork, repurposing cheap and disposable materials into brand new technologies. Its physical composition (body parts, human-like frame etc) also showed Paik’s desire to humanise his robotic creations.

How was the photo or video published?

The robot itself was published with the intention to be ongoing. Paik had an idealistic view of the future of modern robotics, and so wanted his robotic creations to be changing constantly. He did not view k-456 as an inert invention, but rather something that could be refashioned or constantly re-modelled if he so desired. There were elements within the robot that were published traditionally however, as the robot played audio recordings of JFK speeches through a speaker. These would have been captured with a microphone during his election campaign / presidency and Paik took them, presumably from a Creative Commons or public audio library.

How was the photo or video distributed?

The robot was originally distributed to the public via street performances, but then it was also used as part of the Robot Opera at Judson Hall in New York in 1964. It also featured in a series of performance exhibitions throughout the ’60s. It lay dormant for quite some time, but then returned to the public sphere in 1982 when Nam June Paik had their first museum exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. During this exhibition, Nam June Paik took K-456 onto the street and orchestrated what he described as an “accident” where the robot was made to cross 75th street and was struck by a car.

References:

Artelectronicmedia.com. (2020). Robot K456 – Art And Electronic Media. [online] Available at: http://www.artelectronicmedia.com/artwork/robot-k456/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2020].

cyberneticzoo.com. (2020). 1964 – Robot K-456 – Nam June Paik (Korean) & Shuya Abe (Japanese) – cyberneticzoo.com. [online] Available at: http://cyberneticzoo.com/robots-in-art/1964-robot-k-456-nam-june-paik-korean-shuya-abe-japanese/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2020].

Gagosian Quarterly. (2020). Life and Technology: The Binary of Nam June Paik | Gagosian Quarterly. [online] Available at: https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2018/10/16/life-and-technology-binary-nam-june-paik/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2020].

Tate. (2020). Nam June Paik – Exhibition at Tate Modern | Tate. [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/nam-june-paik [Accessed 10 Feb. 2020].

The Art Story. (2020). Nam June Paik Art, Bio, Ideas. [online] Available at: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/paik-nam-june/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2020].