In this text, psychologist Howard Gardner suggests five types of minds that he believes we need to take on in order be successful in the future. Relating to mental attitudes opposed to skills and knowledge, the five minds he asserts are:

1. The disciplined mind – one that holds the ability to persist to attain a specific skill or certification

2. The synthesizing mind – one that makes connections between disparate pieces of information

3. The creating mind – one that comes up with new ideas and offers fresh outlooks towards things

4. The respectful mind – one that takes special consideration of others, welcomes human differences and tries to work effectively with all kinds of people

5. The ethical mind – one who is conscious of how their actions and work affects society

He then goes on to critique the education sector and its narrow focus on science and technology. Her primary argument is that if the education does not broaden its curriculum to encompass social sciences (such as arts, humanities, civics, ethics health and safety) then individuals will never be able to adopt the five mindsets that will enable them to succeed.

Upon initial thought, I was transported back to high school and the familiar phrase ‘when are we ever going to use this in life?’ entered my head. In some respects, this age-old question has some level of merit to it, as realistically we rarely revisit our high school science and maths unless we choose to go down that path. The formal education system is quite traditionalist in the sense that the curriculum has changed very little in the last 50 or so years in light of the fact that our society has changed in such drastic ways.

However, relating the text to my own experience I would have to disagree with the apparent exclusivity of formal education. At my high school, we were offered a range of social science subjects in addition to traditional science and technology-related knowledge. In terms of the respectful and ethical minds – which are more so associated with human relations – we also undertook workshops and activities that had the end goal of improving our social skills and ability to work with one another. While we never learnt to do our taxes and how to truly ‘adult’ as they say, I feel like I came away with a breadth of knowledge that has certainly helped me to acquire the five mindsets, or at least in getting a taste of each.

Overall, I saw the point that the author was making but I do feel as though there were some gaps in their discussion. Perhaps the education system is making progress, but still has a long way to go.

This reading poses some interesting questions and assertions about our relationship with time as a result of living in an acceleration society. By ‘acceleration society,’ the author implies the rapid rate in which technological advances are occurring and effectively changing the way we choose to allocate and utilise our time during both work and leisure.

It is interesting to acknowledge the fact that although digital technologies are essentially designed to save us time, they do not always have this effect. It’s as if these technologies place a greater expectation on workers to get more done in a day than what was once expected without said devices. In saying this, the fact that time is money induces the need for maximum efficiency and productivity within as little time as possible, which while this can potentially increase leisure time, it can also make us feel more pressured and rushed.

Further, the constant connectivity that these technologies enable makes it harder to (literally) switch off from work, which can interfere with our leisure time. Elaborating on this, Wajcman acknowledges how the abundance of ICTs affects our leisure in the sense that we are constantly renewing our devices, which requires a regular investment in new skill acquisition. She also highlights the fact that although new while modern autonomous technologies, such as driverless cars and smart kitchens, promote themselves as being time-saving and time-efficient devices, they will not necessarily solve our time-related problems.

This reading puts forward some interesting ideas in relation to the work/life balance. While it does not give us the answers, it certainly positions us to think about our time-related priorities and the pace of which we wish to live our lives.

In this text, Cal Newport presents an interesting angle on particular attitudes and approaches towards work. Specifically, he reveals the mindset that he believes workers in all fields must assume in order to build a compelling and satisfying career – that is, the ‘craftsman mindset.’

The craftsman mindset is based on the idea that your skills and output trumps all, and by focusing on these assets you will ultimately lead a happy and fulfilling career. Newport uses musician Jordan Tice as an example, as he is so focused on his craft and skill set that he remains incredibly humble and content with what he is doing. By focusing purely on his music in attempt to create the best result possible, he does not let questions of self-validity cloud his view. Newport also acknowledges the career and tact of comedian and actor Steve Martin, who worked at his stand-up act for a solid 10 years before achieving his eventual success. Newport uses Steve Martin’s quote ‘be so good they can’t ignore you’ to demonstrate the strength of the craftsman mindset in achieving your goals.

Conversely, Newport highlights the fact that although the ‘passion mindset’ is perhaps more commonly held, it is much more problematic. According to Newport, the passion mindset focuses on “what the world can offer” you, and is based on the premise that “people thrive by focusing on the question of who they really are – and connecting that to work that they truly love.” However, Newport asserts that when you focus purely on what your work offers you, you will effectively start to concentrate on the aspects you don’t like about it, which will lead to unhappiness. Further, workers with the passion mindset also deal with the struggle of attempting to answer life’s impossible questions, e.g. ‘who am I’ and ‘what do I truly love’. He suggests that the inability to answer these questions will lead to prolonged confusion and self-doubt.

Whilst I certainly understand the worth of focusing on your outcomes over life’s hindering questions, I feel as though passion still comes into the equation somewhere. At some level I tend to agree with the counterargument, that is, that pre-existing passion can fuel the craftsman mindset. Newport dismisses these arguments as he claims that performers like Jordan Tice and Steve Martin would have sourced their craftsman mindset from a more pragmatic standpoint, such as the need to get by and source an income. But my question is, why would people pursue such uncertain and precarious positions in the first place, if not for passion?

This reading outlines the issues surrounding media-related labour and the blurred lines between flexible working conditions and exploitation. This is immediately relevant for us as I found myself relating to a number of the issues raised, such as the pros and cons of extended low-paying or unpaid internships and the uncertainty of freelance media work. Safe to say this text has made me even more anxious about my future in this field and has positioned me to seriously consider extending my 2017 travel gap year by at least an extra year to further delay facing the harsh reality that is this industry.

Okay, let’s try to be positive here. The benefits of informal work do look good on paper, as indicated by Richard Flordia’s optimistic Rise of the Creative Class. Theoretically, through undertaking informal employment, you can work the hours that suit you and live an autonomous and liberated lifestyle. It is also relatively easy to start doing what you love in order to build your resume if you are prepared to do it for less than minimum wage or for free. In relation to my own life, I’m currently in this position with my recent creation of my own media production business, Elemdee Media. I’ve done some videography jobs for free and others for a small amount, and I’m flexible in the sense that I can edit videos from home and in my own time.

However, it is needless to say that informal employment in the media field has some serious downfalls. To name a few, there are no minimum wages, you run the risk of being exploited and you are usually either overworked or out of work entirely. Unpaid internships and months doing informal freelance jobs do not guarantee eventual job security or formal wages. If all this wasn’t enough, it is especially difficult for women to secure formal work in this field. Based on these facts, I tend to think Bakker’s description of this current state of as ‘digital sweatshops’ is sadly pretty accurate (2012). Additionally, the current nature of informal work also puts those in more formal 9-5 jobs in jeopardy as more and more unpaid ‘contributors’ may threaten the need for their full-time position all together.

Lobato and Thomas try to keep our pride intact by proposing some solutions for these issues faced by creative workers. They assert that in order for informal work to be ethical and fair, clear differentiation of intent needs to be identified (e.g. between unpaid internships with future career in mind and hobbies undertaken purely for self-satisfaction) and appropriate regulation needs to be put in place. In an ideal world, we need “the creation of regulatory systems that enable the most productive and rewarding kinds of formalities and informalities to coexist.” Easier said than done, but one can dream…

In this week’s text, Chris Lederer and Megan Brownlow outline some of the recent shifts in the Entertainment and Media (E&M) industry that, if utilised effectively, have the capacity to contribute to the continuing sustainable growth of the field. In this post, I will elaborate on two of the shifts they identified that were of particular interest and relevance to me.

One of the shifts mentioned was the role of youth as an increasingly influential demographic for the E&M industries. According to their research, there is an obvious correlation between markets with higher populations of youth and those with high E&M growth. This does not surprise me, as increasingly we see youth today adopting new technologies and platforms ahead of older generations. Not only are we quick to jump on the latest technological bandwagons, but we are also the generation of multi-taskers, with phenomenons of double- and even triple-screening becoming a daily habit. As youth today have growth up with the Internet and technological devices such as smart phones and tablets, they are inherently more responsive and open-minded to new technologies that might arise in the future. Marketing to this demographic is thus of vital importance to E&M companies not only due to the fact that they are bringing in more revenue, but also because they are ultimately the future of consumerism.

source: sheknows.com

Lederer and Brownlow also claim that contrary to many contradicting opinions, “content is still king.” This is reassuring to us as media practitioners, as although new technologies and platforms create new and exciting ways of consuming media, they would not get far without the high quality content (which is where we come in) to distribute to consumers. For example, if Netflix had mind-numbingly awful content, people are not going to respond positively despite the convenience and affordability of the platform itself. Further, the section on tailoring universally appealing content for local markets is also an interesting concept to think about. When we think of greatly successful content, we often determine this by its international reach. But international reach is in fact more complex than what we might initially assume. Lederer and Brownlow highlight the benefits of “blending international reach and local focus.” This relates to shows that have begun in one country and are adopted and produced by another with their own national flare, e.g. talent shows, dating shows and even cooking shows. These programs are commonly successful as the style and format has already been tried and tested, and the localised focus helps to resonate more with domestic audiences.

This reading presented some relevant points that are helpful in understanding the areas to tap into in order to be successful in this constantly changing landscape. Although these opportunistic areas might be limited to the next 5-10 years, they certainly provide a good starting point.

After reading the selected excerpts of Klaus Schwab’s The Fourth Industrial Revolution, I felt a strange mixture of excitement and fear. There’s no questioning the fact that recent technological developments and future trends have and will drastically alter the state of the world that we live in, but whether it be for the better or worse in the long run is still up for debate.

Schwab begins by identifying the physical, digital and biological drivers and megatrends that have essentially crafted the ‘fourth industrial revolution.’ It’s amazing to consider the fact that automated cars might become the norm, that we as humans might collaborate with robots on a regular basis, and that synthetic biology could repair injury and eliminate disease. Most relevant to the media industry is of course the growing phenomenon of digitisation. The Internet, for example, has reinvented the state of the economy, changed the nature of work and has provided individuals with a modern sense of community and an opportunity to make their voices heard. At surface value, these innovations are mind-blowing and have begun, and will likely continue to, benefit our economy and quality of life.

However, Schwab not only draws attention to the advantages of the revolution, but also the undeniable implications. One of the things that stood out for me was the inequalities that would be further exacerbated by the continued proliferation of digital technologies. Developing countries and social groups of a lower class might become further ostracised as they do not have the resources to gain access to such technologies and information. Additionally, those who are tech-savvy will inevitably have significant advantages over those who are not. It becomes the responsibility of the government to step in and improve accessibility, availability and education in order to overcome these issues – but this is easier said than done.

Further, the effects of the revolution on society’s behaviours and attitudes are also a cause for concern. Schwab identifies how synthetic biology may lead to the standardisation of designer babies. This immediately made me think of the film Gatacca (1997), a sci-fi drama in which individual’s capabilities are determined strictly by their genetic makeup. While at the time of its release the concept was unimaginable, after reading this text, it doesn’t even seem that far-fetched. The fact that science fiction could become a reality is slightly terrifying to say the least. Schwab also highlights how the increased use of digital devices might lead to a decline in face-to-face sociability and the ability to feel empathy. Sadly, I feel as though we are already headed in this direction as our digital devices have essentially become an extension of our bodies and identities. The internet and social media has altered our lifestyle so much in such a short span of time that I’m kind of scared to see where it takes us next.

This text was certainly eye opening and positioned me to discover that I have a lot of mixed feelings towards the subjects covered. Innovation and enterprise are of course essential to our economy moving forward, but that’s not to say they don’t come without their complications.

Statement of intentions

For the upcoming media exhibition day, we have been asked to provide a one-minute screener for the presentation, as well as a visual poster, a page on the Writing For Film blog and a compilation of longer clips for the exhibition. Bonnie and I have divided said deliverables fairly and equally in order to best showcase our hypothetical feature, Black Flat. I will endeavour to put together the one-minute screener, Bonnie will make the poster and together we will write the page for the blog. I hope that our work is well received by the media community and the amount of effort that went in is recognised.

Reflective report

The media exhibition day was a fantastic opportunity to not only showcase our own work, but also see what the rest of the cohort has been up to. And who’s gonna say no to free nibbles and drinks?!

As for Squadron’s contribution, Bonnie and I divided the deliverables fairly and equally as planned. I was responsible for the one-minute screener, while she took on the Black Flat poster. We were luckily both able to churn these out pretty quickly and were satisfied with the quality of each. Bonnie’s poster looked a treat, featuring a number of screen grabs, relevant imagery and succinct descriptions of our objectives and practices.

My experience editing the screener was actually really positive and I was pleased with what I was able to create in a short span of time. While there was mixed suggestions as to what we could include in the screener (clips, text, voiceover etc.), I decided to focus on creating something of a high quality that would be engaging and intriguing for the audience. With that in mind, my aim became to merge our scenes together into a trailer format in a way that showcased the best of our work, whilst encapsulating the eerie vibe we originally set out to establish. I was glad I got the opportunity to do this as the outcome was in fact more so what Squadron intended to create from the beginning of our project. As seen in the presentation, Jackson and I only had time to piece together the two complete scenes in their entirety, and we did not get the chance to take this extra step to merge the two scenes together. Thus, the exhibition presented perfect opportunity to undertake this step, as I knew we had some great moments that would suit the trailer format seamlessly.

In terms of the stylistic tools utilised, I made the effort to colour grade and add music and text to the screener. As we did not have a chance to properly do these things for our complete scenes for our week twelve presentation, I was keen to see to what extent they would transform our footage. I believe the colour grade really tied it all together, with the blue hue giving it a cinematic feel and creating the ideal dark and creepy mood. In addition, Jackson’s score had a similar effect: in its complete form it was ideal for the length for the clip, and I used it as to guide the pace and build-up of the trailer. The titles, albeit cliché, also served to enhance the dramatic nature of the screener and worked well to transition from one scene or moment to the next.

I would say that the most challenging aspect of editing the screener was trying to condense our footage down to the one-minute mark. There was lots of great conversation between Emily and Ted that I was forced to cut out, but I was conscious to include the highlights whilst ensuring it still flowed in a logical order. Whilst I was in the suites, Paul stepped in to give me a hand with some of the technical aspects, which was a big help as it opened my eyes to some different ways of doing things. Putting this screener together ultimately tested my skills as a solo editor, but I think I was able to do did a decent job. I certainly learnt a lot about pacing, titles, transitions and colour grading in the process.

Bonnie and I also collaboratively wrote the blog post for the website through the use of a shared Google document. We used the script for our week twelve presentation as a template then edited it accordingly to provide a more general, well-rounded insight into our production practice. We also added our film poster and a few behind the scenes photographs to enhance the visual aesthetic of the page, as well as of course our three final film prototypes. While it was hard to gauge the level of engagement of onlookers with our film, based on comments from my peers I think it was quite well received. It’s always nice to hear positive feedback on something you’ve worked so hard on, so that was a bonus for me.

Upon reflection, the presentation and exhibition was a great opportunity to showcase our work to like-minded others. As a class, I believe we collectively had some strong outcomes that we can be truly proud of.

The artefacts

Our screener/teaser trailer can be found below, and the blog post for the website can be found here.

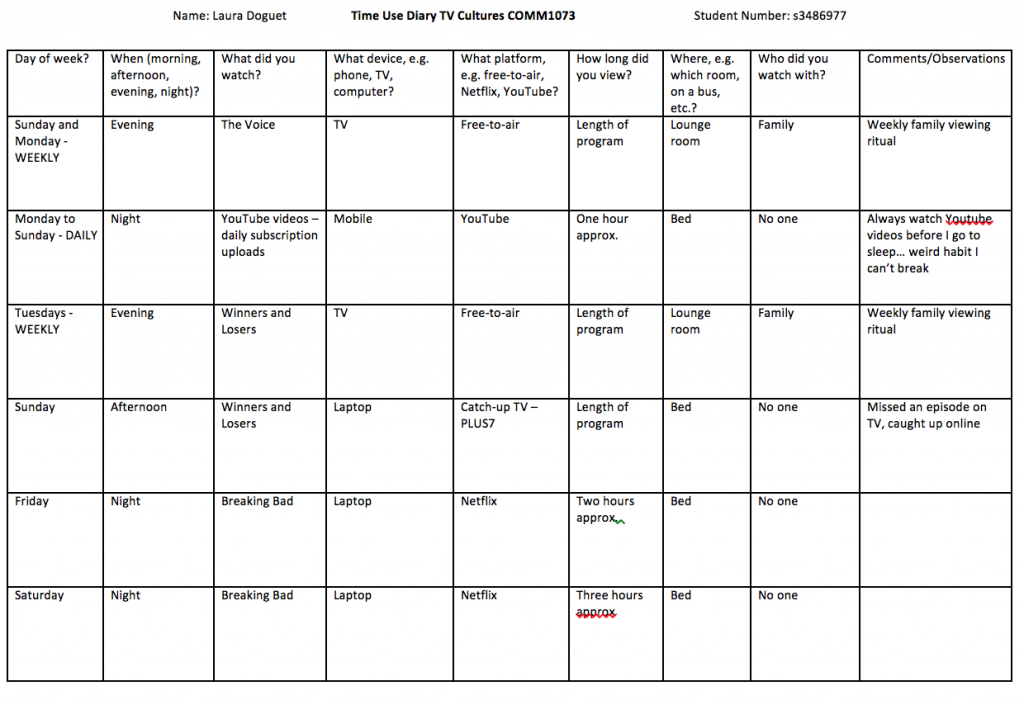

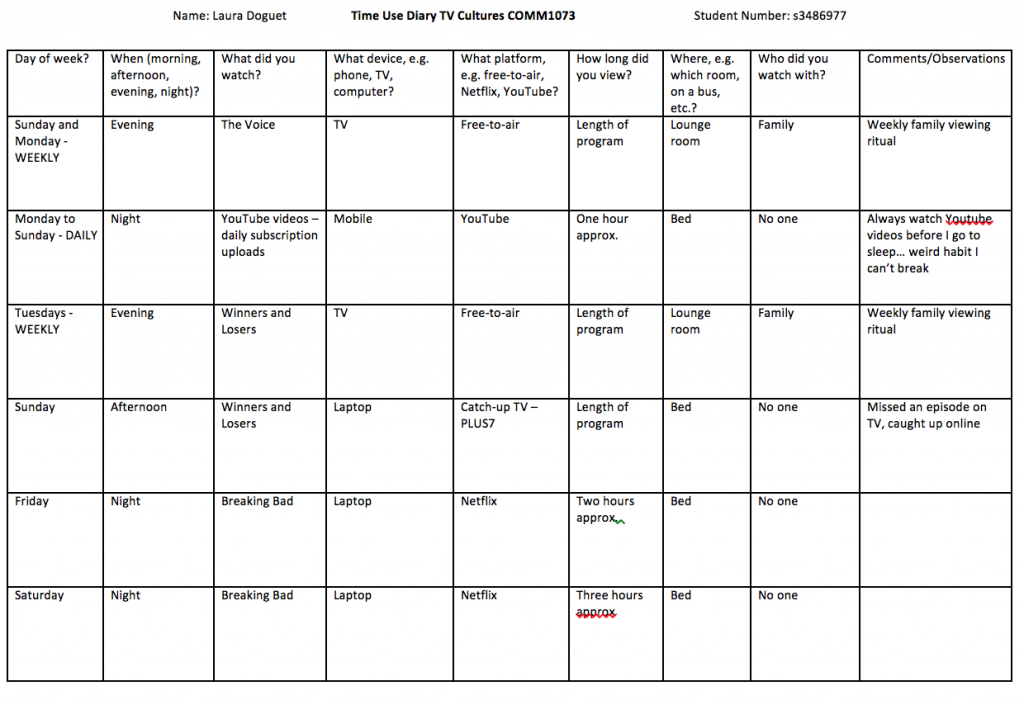

Keeping up with the time-use diary has taught me a lot about my viewing habits over the past semester. Based on the programs, platforms and devices I have engaged with, I will analyse my viewing in terms of the following four areas: YouTube in the place of TV, binge-watching on video on demand, family rituals and the power of televised movies.

YouTube is a huge weakness of mine and, as evidenced in my time-use diary, I spend more time on it than any other viewing platform. I have many subscriptions that I engage with regularly – primarily vloggers– and I find it difficult to lessen that engagement once engrossed with their channels/lives. Through the direct address of their viewers, vlogs effectively “establish conversations between the vloggers and their audience” (Aran et. al 2015). As a result of this, viewers feel connected to vloggers through them being their authentic selves and the affective dimension of their expression (Soelmark 2015). I think I also find myself spending more time on YouTube than watching TV or Netflix because watching one eight-minute video on my phone feels like less of a distraction when studying than a 40-minute episode of a TV series. However, this simply means I end up watching more YouTube videos, so either way I end up being counterproductive. Alex Juhasz describes YouTube as a “private postmodern TV of distraction,” which has proved accurate in my experience.

Binge watching is another mode of viewing which I found myself falling victim to. While I usually try to refrain from giving into the temptation during uni, I fell into a relapse over the mid-semester break as I watched a solid eight episodes of Breaking Bad in a single day (a little late to the game, I know). Lisa Perks refers to binge watching as a “media-focused floating holiday, one that affords a break from everyday drudgery through an immersive escape to the fictive world”(2014). This notion sums up my experience with binge watching as I love being so immersed in a program that you feel the need to watch consecutive episodes. Perks also notes that this mode of watching can be either motivated or accidental, and ultimately made easier by streaming services. Netflix and the like enable instant gratification as they immediately load and play the next episode before you have time to re-evaluate your life.

I also became aware of the fact that the little amount of traditional television I watch is almost always with my family. My parents and I tend to find ourselves getting hooked on two genres: Australian dramas and competition reality shows. We engage with these programs as per their weekly scheduled slot and work our nightly routines around their basis. While some scholars argue that television is disruptive to the family’s socialness, others have more of an open mind suggesting it can bring the family together and provide a topic of conversation, rather than supplant it (Morley 2005). Viewing in this sense for me is as much about spending the time with the family as it is about the programs themselves.

Finally, the last form of televisual content I found myself engrossed by was televised movies. I have a love-hate relationship with televised films as so often I wind up watching movies that I either own on DVD, or that I’ve seen many times before. For example, the other night I returned from work to find the Bourne Identity screening on Channel Nine. Despite being a quarter of the way through and aware of the fact that we own it on DVD, I persisted to watch the film on television, ads and all. While I acknowledge the absurdity this viewing habit, there is just something strangely appealing about films that are slotted into the daily television broadcast. It feels like more of a ‘special event’ than if I was to fish out the DVD or source the content online.

Evidently, the time-use diary has led to some interesting realisations about my viewing practices – the good, the bad and the questionable. It’s interesting to note the shift towards video on demand services and consequently the lessened level of engagement with traditional television. This is likely indicative of a broader cultural shift in viewing habits resultant of the evolution of viewing devices and platforms. Nevertheless, the traditional television still holds merit in the family household and will likely continue to be relied upon for years to come.

References

Aran, O, Biel, J & Gatica-Perez, D, Broadcasting Oneself: Visual Discovery of Vlogging Styles, IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, Jan. 2014, Vol.16(1), pp.201-215

Laytham, B 2012, ‘Youtube and U2Charist: Community, Convergence and Communion,’ IPod, Youtube, Wii Play: Theological Engagements with Entertainment, Wipf and Stock Publishers, p.50-71

Morley, D 2005, ‘Television in the family,’ Family Television: Cultural Power and Domestic Leisure, Routledge, p. 7-29

Perks, L. 2014, ‘Behavioural Patterns,’ Media Marathoning: Immersions in Morality, Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, p. 15-39

Soelmark, N 2015, ‘Circulating Affect’, Structures of Feeling: Affectivity and the Study of Culture, Berlin, Walter de Gruyter, p.199-255

When we think of the terms ‘fan’ and ‘fandom,’ adjectives along the lines of obsessive, crazy and hysterical tend to immediately spring to mind. But is it necessary for individuals to align with these stereotypes to be considered a fan, and how has fan culture and the associated stigma developed with the evolution of the Internet? For the purpose of this blog post, I will be investigating the nature of media fan culture in relation to the classic US sitcom, Friends.

Known and loved by many, Friends revolves around a circle of friends living in Manhattan who face the everyday struggles of adulthood. With elements of love, loss, family and of course friendship at its crux, Friends, created by David Crane and Marta Kauffman, went on to become one of the most popular series of all time (Davies 2013). While the rave reviews and ratings at the time of the show’s inception were indicative of its success, its ability to stand the test of time to this day certainly says something about the loyalty and dedication of both its old and new fans alike.

Image source: tv.com

The term ‘fan’ refers to “somebody who is obsessed with a particular star, celebrity, film, TV programme, band; somebody who can produce reams of information on the object of their fandom, can quote their favoured lines or lyrics, chapter and verse” (Duffet 2013). Hardcore Friends fans uphold a level of devotion in line this definition: they can watch episodes over and over again and still find them hilarious, have the ability to relate every life situation to a Friends episode and quote all of the characters word-for-word.

Fandom, on the other hand, relates to the collective of individuals who hold a shared level of devotion and mutual interest towards a popular culture artefact, often likened to a modern cult following (Ross 2011). A sense of community and belonging can derive from participating in a fandom and some argue that fans are “motivated as much by the values of collective participation with others as by devotion to the persona [itself]” (Horton & Wohl 2006). However, despite the positive outcomes that result from their participation and the growing acceptance of fandom as a permanent sub-culture of society, negative connotations persist to follow in their wake. Henry Jenkins claims that fandoms are “alien to the realm of normal cultural experience” and “dangerously out of touch with reality” (2012), while Matt Hills classes them as “obsessive, freakish, hysterical, infantile and regressive social subjects” (2004). Although these are somewhat accurate representations of your stereotypical ‘Directioners’ and ‘Beliebers,’ I would argue that it is not reasonable to class Friends fans in this condescending regard. When a program is widely considered to be high quality and in good taste, it deserves to have people follow it, enjoy it and actively engage with the program and like-minded others.

While the term is perhaps more commonly used and referred to in this generation, fandoms have existed in our society since the early 1900s (Duffet 2013). It is their means of participation since the advent of the Internet, however, that have taken on new extremes and thus transformed their image. Friends began in 1994 and concluded after 10 strong seasons in 2004. For the vast length of this time, the Internet was not readily accessible and today’s most influential social media platforms did not exist. Nonetheless, the fandom found other ways to express their love for the show. For example, the water cooler effect was in full swing as fans would discuss happenings of the program the next day at school or work; individuals could purchase VHS versions of the show or DVDs when they eventually became available for additional content; or, they could engage with the occasional article and/or interview published in print media. Today, Friends fan culture has been revived and revolutionised through the integration of content across an array of different mediums online. There are social media accounts and pages solely dedicated to the program, memes on every corner, fan fiction, fan art, online quizzes and the list goes on. This proliferation of content has likely ignited a new wave of Friends fans, whilst further fuelling and satisfying the love of those who have been there from the start.

Evidently, the Friends fandom has not only stood the test of time, but they have also adapted to the changing ways of the media landscape in their expressionistic endeavours. Despite the cynicism that comes hand in hand with fandoms, Friends fans remain civil and untouched by the negativity knowing that their love for the program is justified.

References

Davies, M 2013, ‘Friends forever: Why we’re still loving the hit TV show 20 years on,’ Daily Mail, October 20, viewed 23 October 2015, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you/article-2465332/Friends-Why-loving-hit-TV-20-years-on.html>

Duffet, M 2013, ‘Introduction,’ Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture, Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 22-76

Hills, M 2004. ‘Defining cult TV: texts, inter-texts and fan audiences,’ in A. Hill and R. Allen, ed., The Television Studies Reader. New York: Routledge.

Horton, D & Wohl, R 2006, ‘Mass Communication and Parasocial Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance,’ Participations, Volume 3, Issue 1, viewed online October 20 2015, <http://www.participations.org/volume%203/issue%201/3_01_hortonwohl.htm>

Jenkins, H 2012, ‘“Get a Life!” Fans, Poachers, Nomads,’ Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (2nd Edition), Routledge, p.9-50

Ross, S. 2009, ‘Fascinated with Fandom: Cautiously Aware Viewers of Xena and Buffy,’ Beyond the Box: Television and the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, p.127

Although reality television is one the most stigmatised and controversial genres on our screens, it is also one of the most successful. Reality TV encompasses elements of the information, entertainment, drama and documentary genres, and typically presents itself as an entirely truthful, albeit dramatized, representation of events. However, many factors contribute to the constructed nature of the genre, which raises issues of authenticity and ethics. For the purpose of this blog, I will be analysing these matters of in relation to possibly the most-talked-about program on Australian television, The Bachelor.

Reality TV can be broken down into a number of sub-genres, yet four foundational elements remain the same: ordinary people are placed in a contrived situation to face some kind of challenge surrounded by cameras (Kavka 2012). Despite its popularity amongst viewers, critics have attacked the reality genre since its advent for being “voyeuristic, cheap and sensational television” (Hill 2004). However, audiences are not deterred by these appraisals and are instead attracted by the light-hearted, addictive nature of the programs. Viewers find gratification in the ability to relate and emphasize with those similar to themselves, and are able to satisfy the inherently curious nature of the mind by making social comparisons (Krauss Whitbourne 2013).

Originally airing in the US, The Bachelor franchise is a competitive dating show in which one budding bachelor embarks upon a quest for love. A pool of women compete for the bachelor’s heart in the hopes that they will receive a rose and proceed to the next round. Its success has led to many national adaptations of the program, as well as several spin-offs including The Bachelorette, Bachelor Pad and Bachelor in Paradise.

Image source: popsugar.com.au

According to Kavka, at the time of its inception, The Bachelor actually lifted the stigma associated with the reality dating show format by focusing on the ideology of marriage and prospect of finding true love. Its predecessors on the other hand, such as the disastrous Who Want to Marry a Millionaire?, were rightfully considered as a “voyeuristic publicity stunt” (2012). The Bachelor therefore served as a refreshing change of pace as the motivations of the contestants seems authentic and relatable to the middle-class viewer. Participants continuously make comment that they are “there for the right reasons” to reassure viewers and even themselves that they are genuinely there in an effort to find a life partner.

However, The Bachelor, like all forms of reality TV, is still criticized based on the fact that it “deceives audiences into accepting heavily manipulated, edited, and contrived material as factual” (Lumby 2012). While appearing authentic on the surface, The Bachelor utilises a number of strategic, stylistic techniques to further enhance the dramatic nature of the program. For example, the one-on-one interviews with the producer can influence the individual to think or feel in a certain way, and their words can be later taken out of context for dramatic effect. Similarly, the power of editing must not be overlooked as they can use it to deliberately discard material, add melodramatic music and juxtapose particular shots tactically in order to convey a desired mood or message (Barnwell 2008).

The level of influence of the producers remains unbeknownst to viewers and critics alike, making it difficult to identify to what extent the truth has been manipulated. However, the high rate of failed relationships does comply with the perceived fictitious nature of the program, and leads audiences to question whether or not the final declaration of love is staged. The controversy that followed season two of the Australian program, as Blake Garvey proposed to Sam Frost to only dump her six weeks later, is a prime example of how the show, or at least aspects of it, are likely fabricated. Blake’s confessional words of being madly in love with Sam directly contradicted his later comments of why they broke up so soon after. This sent the Australian public and media into a frenzy as they doubted the sincerity of Blake’s words and actions throughout the entire series. While some viewers may have felt cheated by the reveal, the incident did not hurt the ratings of the following series, as well as Australia’s first Bachelorette, featuring Sam herself. If anything, the controversy made audiences more inclined to tune in to see what all the fuss was about (Lallo 2015).

It is difficult to pinpoint to what degree reality programs are fabricated yet it’s impossible to deny the constructed nature of the genre. While The Bachelor seemingly has positive intentions by offering contestants a serious opportunity to find love, the format and set-up of the show inevitably raises questions.

References

Barnwell, J 2008, ‘Post Production,’ The Fundamentals of Film Making, AVA Publishing, p.169-185

Hill, A. 2004, ‘Understanding Reality TV,’ Reality TV: Factual Entertainment and Television Audiences, Routledge Taylor and Francis, p.2-13

Kavka, M 2012, ‘Reality TV,’ TV Genres, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, eBook Collection, EBSCOhost, viewed 27 October 2015, <http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/ehost/detail?sid=01f2959c-0e88-4536-bc4d-2e1a214255ca@sessionmgr4004&vid=0#AN=488681&db=nlebk>

Krauss Whitbourne, S. 2013, Who Watches Reality Shows, and Why? weblog post, May 21, Psychology Today, viewed 23 October 2015, < https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/fulfillment-any-age/201305/who-watches-reality-shows-and-why>

Lallo, M. 2015, The Bachelor 2015: Why are we all so smitten with The Bachelor?, Sydney Morning Herald, September 17, viewed 24 October 2015, <http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/the-bachelor-2015-why-are-we-all-so-smitten-with-the-bachelor-20150917-gjomgp.html>

Lumby, C. 2012, ‘Reality TV,’ Encyclopaedia of Applied Ethics (Second Edition), Academic Press, p.734–740