The judicial precinct of inner city Melbourne has very recently come under scrutiny, particularly the area located on the corner of Russell and La Trobe Streets. The building currently standing there is Building 20 of my own university, RMIT, and as with most other RMIT buildings it was not built for the purpose of tertiary education. The site was built upon first in 1842 with a structure much more modest than the one existing today for the purpose of hosting the Supreme Court of Victoria. A few years later saw the building become the Court of Petty Sessions before being completely replaced by the Magistrates’ Court in 1910. This court is the same stately building that stands on Russell and La Trobe as a part of RMIT University. The photo below shows it in its early years, when the streets were emptier and blocks were undeveloped.

Building 20 stretches along both streets for nearly half a block in either direction and holds an impressive height for a building over one hundred years old. Visiting in the late afternoon allowed me to view the foundations in a delicate, warm lighting that flattered its architecture and played down the grime accumulated on ledges that were hard to reach.

It personified an old and proud man who has reached the end of his working abilities, not necessarily providing a welcoming atmosphere but standing in patient silence. Had I been able to enter the building to explore, I’m sure it would have been just as grand on the inside

It personified an old and proud man who has reached the end of his working abilities, not necessarily providing a welcoming atmosphere but standing in patient silence. Had I been able to enter the building to explore, I’m sure it would have been just as grand on the inside  but that is only speculation seeing as it is now a building employed by RMIT. I felt as though the space was private and sacred, similar to a library. Trees surrounding the building helped mask the signs of street life and gave off an autumnal feel – the lighting was very rich (though the photos don’t show it) and served to highlight the delicate balance between care and neglect. I felt like I could imagine how stately it would have been as the Magistrates’ Court. You can definitely see the history in the building, particularly when you compare the archway to this sketch of it below.

but that is only speculation seeing as it is now a building employed by RMIT. I felt as though the space was private and sacred, similar to a library. Trees surrounding the building helped mask the signs of street life and gave off an autumnal feel – the lighting was very rich (though the photos don’t show it) and served to highlight the delicate balance between care and neglect. I felt like I could imagine how stately it would have been as the Magistrates’ Court. You can definitely see the history in the building, particularly when you compare the archway to this sketch of it below.

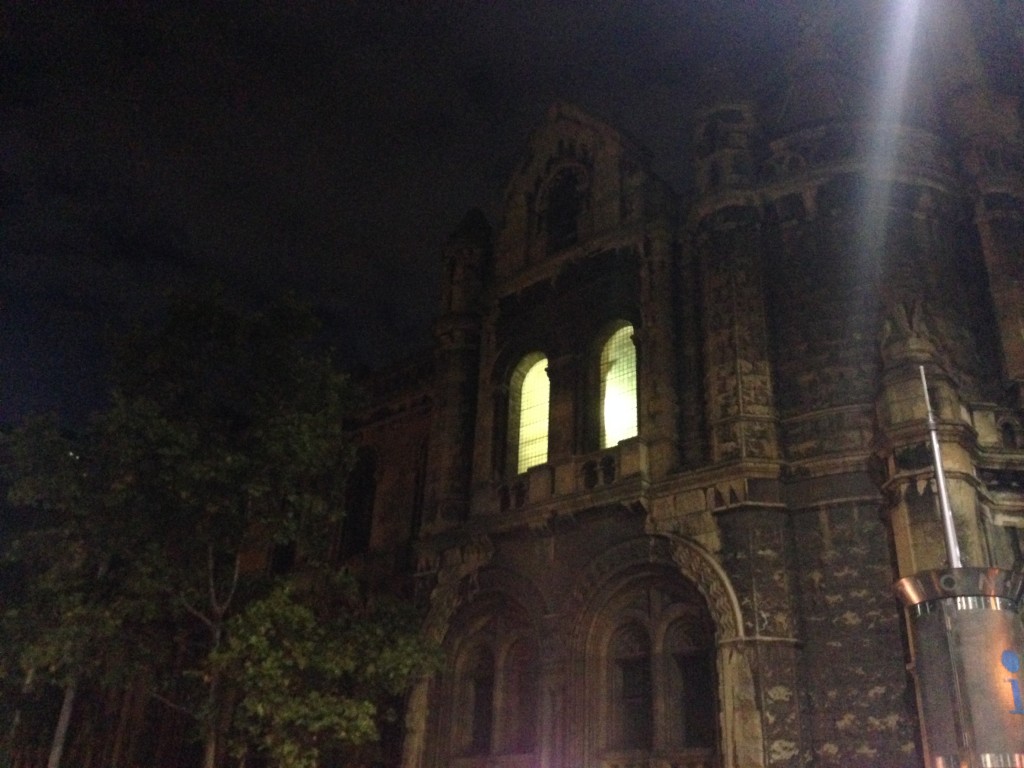

Night time was a very different story. Going off the photos, I wouldn’t have immediately placed the sketch as the same place. Viewing buildings in darkness can have a very intimate effect but that is not the case with Building 20 and it’s definitely due to its structure. An imposing building even in the warm afternoon light, Building 20 looks like the intimidating court where many people were sentenced harsh punishment it once was. Behind the walls of the court are notable ghosts – Ned Kelly was sentenced to death and Collin Ross was punished for crimes he never committed. However, there was hardly any sign of activity or life within the thick walls and I felt quite alone though the street was busy.

Night time was a very different story. Going off the photos, I wouldn’t have immediately placed the sketch as the same place. Viewing buildings in darkness can have a very intimate effect but that is not the case with Building 20 and it’s definitely due to its structure. An imposing building even in the warm afternoon light, Building 20 looks like the intimidating court where many people were sentenced harsh punishment it once was. Behind the walls of the court are notable ghosts – Ned Kelly was sentenced to death and Collin Ross was punished for crimes he never committed. However, there was hardly any sign of activity or life within the thick walls and I felt quite alone though the street was busy.  The trees block out light from the street so the shadows are quite deep and eerie. Standing inside the archway no longer made me feel pensive, instead I was uneasy. There was nowhere to stand that didn’t seem exposed yet it still seemed like something could be hiding in shadow. It was an uncomfortable sensation and it was no better on either sides of the building.

The trees block out light from the street so the shadows are quite deep and eerie. Standing inside the archway no longer made me feel pensive, instead I was uneasy. There was nowhere to stand that didn’t seem exposed yet it still seemed like something could be hiding in shadow. It was an uncomfortable sensation and it was no better on either sides of the building.

The morning sun was similar to its afternoon counterpart, though its ambience was closer to that of the night. Building 20 doesn’t have much going for it if it’s only tolerable during a few hours before the sun sets. What was hidden before was now shown in stark contrast, dirt and growths exposed by the bright light. There was activity everywhere on both Russell and La Trobe and it was not conducive to viewing the building peacefully. I couldn’t see the beauty that was there the afternoon before nor the unsettling solemnity from the night and the modern street signs clashed with the old limestone. It was displacing. However, I did finally find refuge in the archway again. Most court sessions would have been held during the day and from the photo below, it seems like they would’ve progressed without having the street bustle interrupt them. This could never been the case now with the constant flow of people walking, talking, taking photos – an audience that is ready to attack whether they know it or not. It made me feel almost sad for the building. No one notices the history hidden behind the walls during the day, and no one dares during the night. If Building 20 were a person, you would break down their walls, but that’s not a viable idea seeing as it is part of the National Estate Register. I’m unsure as to whether Building 20 would be better off celebrating its deep history more or if it will only survive the future by continuing to truly only open up for a few hours every day (weather permitting).

References:

Dalton, Simon. The Old Melbourne City Watch House: Fast-forward to the Past [online]. Agora, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2008: 60-62. Availability: <http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=490096764027465;res=IELAPA> ISSN: 0044-6726. [cited 12 Mar 15]