Chosen scene: opening torture room scene in Slumdog Millionaire (2008, Danny Boyle).

I had to choose a scene from one of my all-time favourite movies. This scene is superbly clever in its quietly intricate manner of construction.

The geniuses behind this scene and film are Danny Boyle (director) and Anthony Dod Mantle (DP), not to mention Chris Dickens (editor), Jean-Clément Soret (colourist), Ian Tapp / Richard Pryke / Resul Pookutty (sound mixers), and Tom Sayers / Glenn Freemantle (sound editors).

I assume that this was one of the scenes that was shot on 35mm film. A lot of of the film was shot on the IT-centric Silicon Imaging SI-2K Digital Cinema camera, which was tactically chosen for a number of reasons: to fit the environmental demands; to allow the crew to enter and immerse themselves in the mobile world at a child’s level; to intimately experience the colourful, kinetic, chaotic feel of India.

The basic story within this scene is that the police inspector wants to know how Jamal knew the answers to the game-show questions – i.e. he thinks that Jamal cheated, so he has held Jamal overnight for torturous interrogation.

A low dolly tracking shot introduces the space to the audience, closely following the police inspector’s heavy footsteps as he opens the doors and enters the filthy interrogation room. The camera is at ground-level and we only see the police inspector’s legs. However, this low tracking shot serves as an establishing shot, revealing all three characters’ positions within the harshly lit room – Jamal and Sergeant Srinivas are in full view in the background, one either side of the police inspector’s foregrounded legs. One key thing about this shot is its hesitancy to reveal all information at once – only the police inspector’s legs are shown, so his identity is momentarily concealed. Another key aspect of this shot is its nauseating closeness to the ground, forcing us to focus on where characters’ feet are – our eyes follow the police inspector’s steps, then meet Srinivas’ feet firmly on the ground, and then our eyes find Jamal’s feet, which hang limply in the air, disorientingly disconnected from the solid ground. In fact, Jamal’s arms extend just outside the top of frame – whatever he is attached to / hanging from is concealed, which makes for an unnerving compositional balance within the frame.

Most of the following shots share similar qualities.

The scene is covered almost entirely in Dutch tilts – the conspicuously askew frames serving to disorient the audience and foster the nauseatingly thick tension. These Dutch tilts also imitate Jamal’s perspective: most are right Dutch tilts, which is the same tilted angle as Jamal’s head during the scene. They create the impression of hanging / having a limp head resting on an arm and seeing things sideways. The high-angle/aerial wide shot is a left Dutch tilt, allowing us to see Jamal’s roped arms as well as the position of the other characters within the room. Dutch tilts are similarly prevalent in the rest of the film, particularly in scenes of high tension and moral disorientation/violation. Dutch tilts are also specifically associated with the character of Salim and his moral decline throughout the film.

What is unusual about this scene is that almost all of the shots include at least fraction of Jamal in frame. In fact, there is only one which does not include Jamal, and that could be seen as a point-of-view shot. Most of these shots contain an almost unnoticeable fragment of Jamal – out of focus body part, obscurely close to the camera, occupying only a tiny fraction of the frame. They’re kind of dirty over-the-shoulder shots, but with only about an eighth of the shoulder; we are watching from Jamal’s side. What makes Jamal’s presence eerily noticeable is that his foregrounded body is swaying as he dangles in the air. One purpose of this emphasis on Jamal’s presence in every shot is to establish that he is an important character and align the audience with his perspective; this is the opening scene of the film (aside from the montage sequence). His swaying figure also works to unsettle the audience. In fact, it’s almost as if Jamal is more of a disturbing prop at this stage, rather than a character. It’s a particularly bizarre atmosphere at the beginning of the scene when the policeman and Srinivas are discussing Jamal like he’s not there, yet there is always a fraction of him in every single shot, swaying in and out of frame, watching their conversation.

Something particularly clever about the cinematography in this scene – and in the whole film – is its perfection of subtle visual concealment. There is an element of concealment in almost every single shot. The roughly shifting focus affords clarity for only part of the frame at a time. The hard, low-key lighting conceals details by casting harsh shadows and highlights across sections of the frame. The close ups conceal wholes – they are intimate shots that hone in on details while omitting the whole picture. These fragmented frames also give us a strong sense of the space from Jamal’s perspective; for example, the lethargic focus-pulling within a shallow depth of field is almost like eyes adjusting feebly in a space where the air is thick and heavy and dense with heat and dirt. These techniques of concealment and frame fragmentation are consistent throughout the whole film. I think that this is ingenious cinematography. Fragments of things are compelling. I’m a big believer in concealment in cinematography.

Shallow depths of field are used for most shots, particularly the OTS close ups. I assume that Dod Mantle used a prime lens with a relatively large focal length and a small F-stop for these shots. Again, this shallow depth of field works to keep things hidden within the frame – we have soft focus swallowing up parts of the frame and dirtying the picture. This is applied to transform Jamal’s body into an obscure, dark, eerily moving shape in the foreground of many shots. The shallow depth of field also helps to build the impression of the atmosphere within the confined room – vision is hindered by the hot, dense, dusty, stagnant air.

Shallow depth of field. Out of focus / obscure Jamal shoulder. (Concealing right-hand side of police inspector’s face as he slowly sways further into frame.)

The editing is cleverly paced. Many of the shots range from 4 to 15 seconds in duration: they are given time to linger. Within this lingering time, the subtle movement within each shot becomes more apparent. We linger long enough to notice the discreet handheld camera movements and consequently feel more intimately involved in the scene space. We linger long enough to see Jamal sway in and out of frame, to watch the highlights and shadows shift over the characters’ moving faces and changing expressions, to give emphasis to characters moving into different areas of frame and in/out of focus.

Police inspector waits for electric current to run through Jamal, then walks from the foreground into the out-of-focus background to continue his interrogation.

Lighting falling on police inspector’s face more fully at a moment when he ducks down to get a closer look at Jamal. High-contrast lighting in this frame: bright face, black background, dark/obscure shoulder.

The cutting often also serves to disorient the audience by switching between dramatically different shot sizes or angles. For example, common shallow close ups are punctuated by the occasional high-angle/aerial wide, which was perhaps also shot using a wide-angle lens to further disorient the viewer with striking visual change. In fact, most of these close ups are on a right Dutch tilt, whereas the high-angle/aerial wide is on a left Dutch tilt – again causing striking visual change when we cut from one to the other.

The scene also cuts between the high-angle/aerial wide and ground-level close ups. What is most jarring about contrasting these shot levels is revisiting the eery image of Jamal’s arms attached to the ceiling, or of his feet floating above ground: being reminded that Jamal is hanging. Despite being dramatically different from one another, both shots are similarly unnerving. In neither do we get a full view of Jamal’s body; we only see its two awkward ends – attached to what it is not supposed to be attached to, and not attached to what it is supposed to be attached to.

What is quite complex throughout this scene is the blocking. The three characters stand at relatively equal distances apart, almost in a circle, and two of them move around and switch positions frequently. As a result, the camerawork and editing seems to regularly break the 180-degree rule. For example, when the policeman runs towards Srinivas with fists bared, we see this from Jamal’s left shoulder: Srinivas on the left of frame and the policeman on the right. However, we then cut to a shot on their opposite side: the policeman on the left and Srinivas on the right and Jamal hanging out of focus in the background. Now we cut back again to the other side of the conversation (possibly the only shot in the scene without Jamal in frame). And then we cut back to the other side again – there’s a pull focus from the policeman and Srinivas to Jamal in the background as he wakes up, delivers lines, and spits out blood. Nonetheless, the shot construction works fabulously well – perhaps because Jamal serves as a kind of anchor in each shot, so we are less disoriented when we switch between different angles and positions in the room.

The hard, low-key lighting in this scene doesn’t so much illuminate the picture as it does dirty the picture. The colour-grading emphasises a palate of sickly brown and saffron hues. High-contrast lighting brings these hues to the extreme ends of their respective scales in order to heavily texturise the frame’s contents. In the CU shots of the police inspector interrogating Jamal, top lighting casts harsh highlights upon parts of his cheeks, nose and forehead, and deep shadows under his eyes and chin. This severely roughens his features. We see the deep creases in the skin around his mouth, the bags under his eyes, the lines in his forehead and between his eyebrows. We see the bristly stubble on his chin. We see the sweat droplets on his skin and clinging to his hairs. As the police inspector moves in speech, the lighting shifts over his face – different parts are illuminated; different parts are hidden in either extreme brightness or darkness. The effect of this chiaroscuro lighting is to unnerve and induce anxiety in the audience about this threatening police inspector character and this confined, uncomfortable space. The audience is directed to sympathise with and invest in the main character of Jamal. In fact, there are moments when the frame is in near-complete darkness but is punctuated by a few small blinding highlights. For example, after Jamal has the electric current run through him, the contrast between light and dark is increased and the visual drama intensified for the right OTS CU shot of the policeman.

The story source of this lighting is the natural sun entering a couple of narrow, grotty windows that sit high up on the wall above Jamal. This (I think) is the only story source of lighting within the room. The significance of this harsh lighting being able to enter the small window/s and inflict great assault upon the characters is reflective of the hostile Indian environment. We are in scorching India: inescapable, intense heat accompanied by unnaturally blinding natural light (which is equally challenging to escape).

Jamal’s face, unlike the police inspector, is lit with softer, duller lighting. Since the story source of the lighting sits behind/above Jamal, he avoids being assaulted by harsh shadows and highlights. He may not be clearly illuminated, but his features appear comparatively softer than the police inspector’s. The audience is encouraged to align themselves with Jamal, the less threatening character.

The saffron glow to each shot is also significant – saffron colours recur throughout the film. For example, the film’s opening shot where Srinivas blows intensely-lit, golden, turbulent cigarette smoke into Jamal’s face. Latika’s costuming: her top in the recurring shot of her at the train station; her scarf during the film’s final scene. The luminescent yellow smoke cloud in the opera scene. What makes the constant saffron hues far more striking throughout the film is their contrast with the jarringly intercut cold, blue-hued shots/scenes of the millionaire game show. The colour saffron is a motif that holds larger significance within Indian culture. Saffron is one of the three colours of the Indian flag, and is also a celebrated colour within Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism religions. The colour signifies sacrifice, courage and salvation – notions very much pertaining to the film’s narrative and key characters. In this scene, however, the saffron lighting primarily works to unnerve the audience in its sickly-yellowy intensity.

To achieve this look for the scene, Dod Mantle probably used yellow/orange-enhancing lens filters as well as yellow/orange gels on the lights. (I’m not sure what sort of lights would have been used though.) In post-production, colourist Jean-Clément Soret would have graded the film to calculatedly balance and then enhance/dramatise this lighting and colouring.

The lighting in this scene works to conceal – in blinding shadows and highlights – rather than to reveal. It works to dirty the picture, rather than to illuminate it. In fact, I seem to be heading in the right direction with my hypothesis about this film’s cinematographic intention of concealment: Dod Mantle stated in a 2009 interview about Slumdog Millionaire that it was his aim to find a way to “withhold […] detail in the shadows and highlights”. (Yay!)

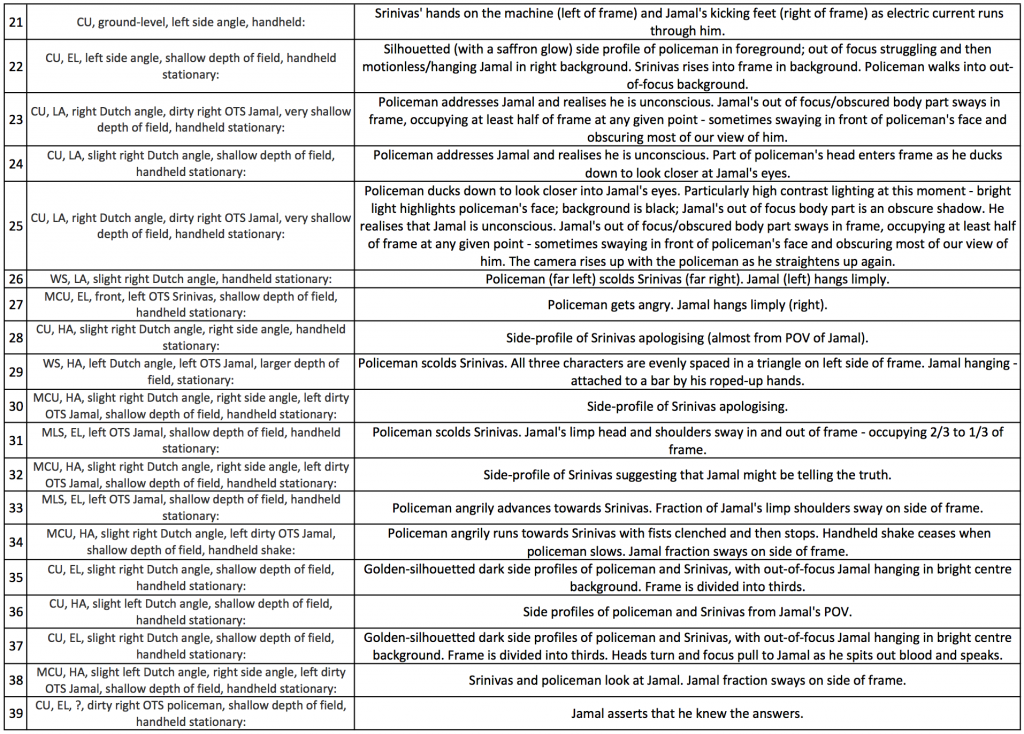

I’ve written a rough list of shots in the scene:

This scene’s sound design is equally as sophisticated as its visual design. It is a design that remains inconspicuous unless you listen consciously. The sounds are layered in a way that builds the feeling of the space with enormous detail and intensity and drama. Reverb is applied to dialogue and sound effects so that these noises echo and seem like they are harshly bouncing off the room’s hard walls and floors and surfaces. When Jamal is tortured, the striking buzz of the electric current breaks the heavy room tone. We hear intimate character sounds like quiet breathing, as well as intimate spot effects like the shuffling of clothes and feet as a character shifts weight from one side to the other in the tiniest of movements. The scratchy whine of ropes bearing Jamal’s weight reminds us of offscreen space not shown in the tight close ups – he is hanging from a rail. It also reminds us of Jamal’s persistent presence despite moments when he is ignored by the others or when he is unconscious (when he is less of a speaking/reacting character and more of a prop in the scene). This recurring rope spot effect works similarly to the compositional pattern of Jamal in every frame. We can even hear – in the characters’ footsteps – the shuffling grit on the floor. All of these intimate sounds paint a detailed picture of the grotty, confined, hot, uncomfortable, hostile space and bring us much closer to the action, story, characters, and spatial feel of the scene.

The ambient sounds further texturise the scene’s spatial dimension. We have birds subtly chirping in unsettling, low-toned, screechy timbres. We have the heavy, low hum of the room tone. We have long, low, panic-inducing, whiney tones that vary in pitch and volume. We have quiet, low, rumbly tones. We have faint high-pitched tones. These sounds are sort of reminiscent of faint yells and vehicle engines and horns – sounds of busy India outside/far away/offscreen. These ambient sounds are also kind of musical in a way, and their layering with the character sounds and spot effects works superbly to govern the changing tension within the scene.

It’s interesting to compare the coverage of this film with that of Boyle’s 127 Hours (2010), which was also shot by Dod Mantle. Visual concealment was similarly prevalent in the camerawork for this film – picture being fragmented by shallow depth of field, close ups, Dutch tilts, harsh ‘natural’ lighting, and so on.

I can also compare this with Besson’s opening scene in Léon: The Professional (1994), which similarly employs cinematographic concealment. However, its style of doing this is purposely self-conscious and conspicuous and almost cartoon-like – it uses all ECUs to reveal only fragments of the larger picture. This is in contrast with Slumdog Millionaire, which employs cinematographic concealment in a subtler, more inconspicuous manner that attempts to suggest the realistic feel of a space. Both films, however, use the technique of concealment partly to build a sense of the main character’s perspective within the space/setting/environment.

This sophisticated scene represents one of my favourite types of cinematography. Boyle and Dod Mantle (and the film’s entire crew) are geniuses. The subtle visual concealment and frame fragmentation is thematically/dramatically/narratively clever as well as visually beautiful. This is another style of coverage that I’m considering exploring for my studio project.

References:

http://www.siliconimaging.com/DigitalCinema/News/PR_01_31_09_Slumdog.html

http://evanerichards.com/2009/56

https://www.nyfa.edu/student-resources/best-cinematography-look-slumdog-millionaire/