Nichols Modes of Documentary: A Case Study of “The Act of Killing”

To observe or to intervene, the question of how filmmakers practice the process of capturing reality on film in order to best portray it back to an audience has been fraught with questions of how much involvement the filmmaker should have since the inception of Documentary Film. It is a question framed by ethical, epistemological, creative and practical concerns, and increasingly, distribution and economic concerns. Nichols considers this question from the former, production centric concerns, in conceiving of his modes of Documentary filmmaking (Nichols, 2010: 142-211). Many of the distinguishing factors between the various modes relates to the level of awareness, amongst the audience, of the camera and the process of filming, whether these modes emerged from the filmmakers’ or the audiences’ desires, is a question of the chicken and the egg, but the evolution continues through each production and it’s consumption.

One point Nichols touches on, is that as audiences’ awareness and comprehension of media techniques grows, their contemporary palate changes, so new modes emerge as a response to existing ones, encompassing what worked about the old modes within applications of new techniques often not previously present in non-fictional film storytelling (Nichols, 1991: 32-38). This intersects the writing of Jones on the blurring line between fiction and non-fiction (Jones, 2005), and Corner on the dramatization of documentary (Corner, 2006: 89-96) seen in modern competitive film and television industry as a necessity to draw an audience, which pulls in a contemporary discussion of the latter aforementioned frame on the discourse of documentary production, that is, distribution and economic feasibility concerns.

It seems to be a growing trend with successful documentaries in the e21C that there must be entertainment value, and a hook. Whether it’s Michael Moore appearing in his films with a megaphone and crime scene tape to take on Wall Street after a Financial Crisis (Capitalism: A Love Story, 2010) or the gimmicky stunt of Morgan Spurlock eating only McDonald’s for 30 days (Super Size Me, 2004). These examples showcase example traits of Nichols’ Interactive Mode with their filmmakers taking part in the on screen action for the audience to clearly see they are shaping the narrative but also interacting with reality. They become actors in their own documentaries, shaping events that reflect something true about the world in a way that has the entertainment value of a fictional narrative that can be packaged and sold. In this way Actor, Performer and Citizen become blurred indistinguishable roles (Jones, 2005).

A film that shows the power of the conventions of the Interactive and Reflective modes when applied to the right topic, in Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing (2012). This film’s subject matter and themes are a dense substance, they’re heavily layered, but the use of some non-conventional tools and a keen awareness and central role of the filming process peels the layers back like the skin of an onion, complete with tears to the eyes of its central characters.

The Act of Killing follows Anwar Congo, and, to a lesser extent, Herman Koto and Adi Zulkadry, as they recount their experiences of killing more than 1000 fellow Indonesians who were deemed “communists” in the Indonesian killings of 1965-1966, which “purged” more than half a million lives. Anwar and some of his fellow “gangsters” and “killers” retell their deeds for the cameras, and in addition produce scenes depicting their memories and feelings about the killings. The scenes are produced in the style of their favourite films: gangster films, westerns and musicals, and are screened back to them during the course of the film.

Today Anwar Congo is revered by Pemuda Pancasila; the Indonesian answer to what you would get if you tried to mask the flavour of corruption of the Somalian Government by fusing the indoctrination and nationalism of Russia’s Nashi, with the right-wing factional and fanatical conservatism and religion of the America’s Tea Party, masquerading in a faux libertarian, and anti-authoritarian rhetoric akin to that of the U.S.’s “Patriot Movement”, and served it on a paramilitary mantra of “Gangsters are free men, and we’re the biggest gangsters” atop a table whose cloth is so proudly soaked in enough blood to make the Khmer Rouge blush. The Pemuda Pancasila grew from the death squads and is so powerful that its leaders include government ministers who are openly involved in corruption, election rigging and clearing people from their land for developers.

The film is profoundly concerned with truth, reality and perception at multiple levels, from its narrative to its form. The Act of Killing doesn’t seek to re-enact the truth of the killings in a historical sense for the audience, it seeks to re-enact the truth of the victors. The film strives to explore the truth of the government absolved killers in the contemporary world, how they go on living, how they feel reflecting on it, and the process of documenting the consequences of these men embarking on a creative process of filmmaking from their experience still manages to capture something of the reality of the killings years later.

History, it is said, is written by the victorious (Attributed Winston Churchill, allegedly inspired by Hermann Göring, 1946), an epistemological contradiction with the Indonesian history told by Pemuda Pancasila becomes particularly prominent to viewer and protagonist as this plays out. If we characterise information as knowledge codified in a form that makes it available to others, such as film, conversation, writing and photography, and accept that knowledge is both belief and truth, for something to be knowledge is must be true and known, and both at the same time, (Spence, Alexandra, Quinn & Dunn, 2011: 23) and take a Rhetorical view of Communication as more than simple transmission of information, but a process in which meaning is created in all the relationships that take place around the communication (Leith & Myerson, 1989), we see that problems arise when the official national narrative, which codifies the knowledge that “communists were cruel, and evil, and had to be exterminated” within public speeches, on national television, in corrupt newspapers, in the official history texts, within propaganda films and in the minds of those who are united by it, diverges from the story that starts to unfold in the scenes produced of Anwar’s memories and feelings, showing perhaps that the death squads were the cruel ones rather than the communists. Some of Anwar’s friends and comrades actively comment that they believed the truth is that the communists were not evil, and that many were not even communists but made to look like it.

The universe is made of stories, not atoms (Muriel Rukeyser, ‘The Speed of Darkness’ 1968). Stories are how we make sense of the world; how we know who’s good and who’s evil; how we know what to expect in the world around us. The importance of film as a tool of story, and the power of film to represent and frame reality is not understated in Act, it is central with both the role Anwar’s production plays in the production of Act as a separate piece. The power of film to shape reality for the audience is also presented with reference to acclaimed Indonesian anti-communist propaganda film, Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (1984), produced some 20 years after the events of 1965-1966 and shown in schools and cinemas nationally since. Particularly insightful was footage of Anwar and Herman watching their dramatizations back on a small television and critiquing it; this vehicle provides a window into Anwar’s view of himself, it glimpses not how the rest of the world sees a mass murderer but how he sees himself and responds to his personal truth.

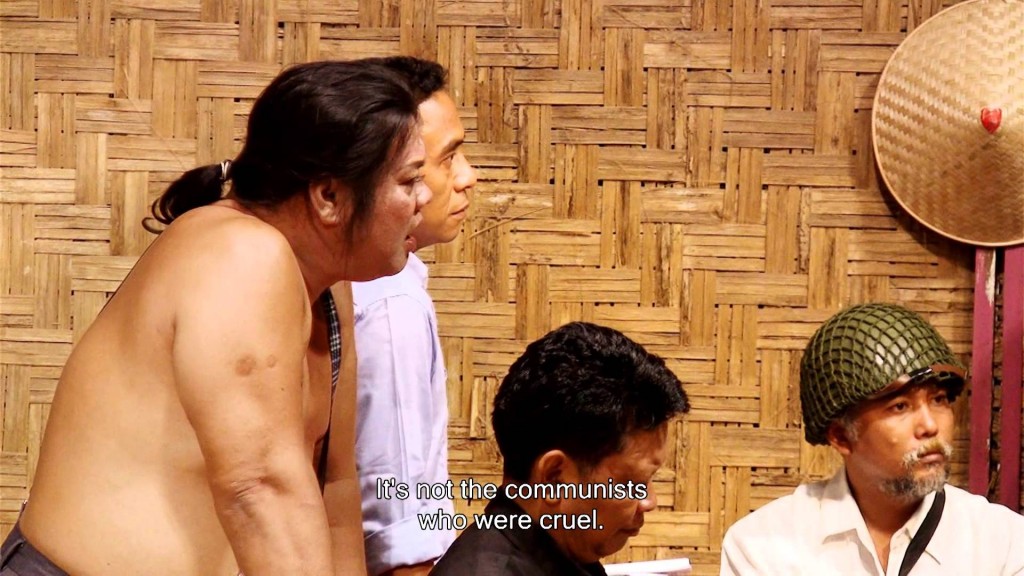

Pengkhianatan is introduced many times into the narrative of Act, initially Anwar and Adi reflect on it with very different commentary, illustrating another concept inherent in the discussion of documentary film’s attempts to present reality; reality is subjective. Anwar states that he feels “proud” of the number of people he killed when he watches that film, he is proud to have exterminated the communists who were so “evil”, and feels “reassured” by the film, and it even alleviates any feeling of guilt. Adi on the other hand believes the film was intentionally designed to make communists appear evil and cruel and uphold this perception to the children of killed communists, he also says this was not the truth of it, he says this was a lie, he goes as far as to admit that the death squads were the cruel ones, not the communists, and is told promptly and quietly by Anwar not to speak out against the film on camera. Adi is undermining a rigid national view of reality that has been written by the powerful neo-death squad Pemuda Pancasila, a reality that helps those responsible stay in power, maintain order and rationalise their crimes. Adi’s disconnect, this alternate reality, and the problems of presenting it to the world, become central questions in the minds of Act’s characters as the film develops.

Pengkhianatan and its anti-communist message, along with the Pemuda Pancasila’s story have become a central part of the imagined nation of Indonesia, and to be part of a nation, all the things that divide us need to be – or get to be – forgotten, and what is focussed on is what unites us (Anderson, 1991: 3-6). The propaganda film for Anwar reassures him that he is part of the national story, and his re-enacted film presents an opportunity for telling that story, he discards alternate stories that may have entered his mind about his actions being immoral in favour of reality as told by the status quo.

For the audience bringing a Western reading, the frame has been laid right from the Act’s opening that these killings are questionable, interviews and statistics have, by this stage, already hinted as mass corruption, and so the underlying knowledge codified in the official story which comforts Anwar is already corrupted and discredited. For an Indonesian audience living under the official story, Act challenges the status quo and requires a consideration of the audience’s position as spectator in ways not too dissimilar to those required by the questions of Kaplan surrounding feminist films strategies for change, and questions of how to present an alternate reality as truth to an audience who’s truth masks the reality (Kaplan, 1983: 44-50). And so we see a film in which multiple truths, multiple realities compete for credibility with our protagonist, an internal struggle that an audience could be hard pressed to extract from a more conventionally expository mode of documentary production, and compete among multiple audiences to reveal the true nature of the contemporary story. The Reflexive and Participatory approach (Nichols, 2010) allows the film to investigate hidden motivations and feelings of characters in a way that would be restricted if the filmmaker was concerned by the audience being aware of the process, unable to acknowledge their own existence.

The niche value of a unique approach in Act is more than a marketing ploy or stunt for entertainment value, although in Act narrative there is exploration of Anwar’s desire to please his friends and audience who prompt him to make something with more gore and sadism than any Nazi film; a real popcorn shovelling shock and awe piece. Through the mode of production Oppenheimer captures a portrait of men who struggle to uphold the external story against their internal reality, glimpsed in moments of reaction and thought, provoked by the captured filmmaking process, many such moments that Anwar himself may have been oblivious to, are highlighted by frame or edit. The distinction between fiction and non-fiction is a constant discussion in Act, from Anwar’s discussion of killing people with wire “in fiction [though] it’s different,” he comments, “I did it in real life” through to after Anwar plays a communist torture victim, and claims he cannot continue due to the overwhelming empathetic feelings he claims to experience, saying watching the scene back that he can feel what his victims felt. Oppenheimer, from behind the camera, states that it was worse for the victims because they knew they were going to be killed, whereas Anwar was only acting. Some of Anwar’s friends state that the killings were wrong, while others worry about the consequences of the story on their public image. Again theme of public reality and private reality emerges and is carried through in a sub-narrative where Herman runs for election to Parliament, he states “nobody believes what they’re publically campaigning for, it’s all fiction, it’s all one big soap opera.”

Anwar’s film project gains media and Pemuda attention and in a scene depicting the Pemuda burning down a communist village, the head of the Pemuda asks that the scene be reshot, to tell the true story, he says he wants to show the communists “humanely” exterminated, because the scene could be bad for the public image of the Pemuda Pancasila if it showed a violent death squad realistically pillaging a village and burning houses. With 3 million Pemuda members and every President of Indonesia since 1965 being an ex-leader of the organisation, the extermination of the communists is as much the national story of Indonesia as the expulsion of the Soviets from Afghanistan was to the ruling Taliban there. Oppenheimer’s film challenges the truth of the nation, dangerously so for many involved in it’s production. The name “Anonymous” appears 49 times in the films credits under 27 production roles, due to fear of retaliation from Pemuda death squad members.

Anwar and Herman according to Oppenheimer were initially supportive of the film once completed, however later reports suggest that both felt betrayed after the film was negatively received in Indonesia and adversely affected their lives. This touches on a whole dimension of ethical questions beyond presenting filmic results to an audience as something other than fiction already raised by this specific film, these additional questions of how the filmmaker relates to the subject could constitute their own essay, though any accusations that subjects felt wronged warrants at least a few sentences. Here the problem grows from the intentions of the subject and the perceptions of the audience, with suggestions that subjects entered the project with the intention to glorify their mass murders, which certainly comes through in a few moments, but Oppenheimer responds: “When I was entrusted by this community of survivors to film these justifications, to film these boastings, I was trying to expose and interrogate the nature of impunity. Boasting about killing was the right material to do that with because it is a symptom of impunity.” In a 2009 study (Aufderheide, Jaszi, Chandra, 2009: 15) of 45 documentary film makers on ethics, filmmakers asserted a primary relationship to viewers, which they phrased as a professional one: an ethical obligation to deliver accurate and honestly told stories. This relationship, returning to the Rhetorical idea of communication (Leith & Myerson, 1989), adds an element of additional meaning to the relationship between filmmaker and subject, and resulted in filmmakers expecting a shift of allegiances from subject to viewer in the course of the film, in order to complete the project. This inherit shift results in Oppenheimer being ethically obliged to the viewer to expose the truth of the subjects divergence and dissent from the official national Indonesian story, leading to potentially negative outcomes for the subject within the context of their social cohesion in the Indonesian imagined nation (Anderson, 1991)

Oppenheimer’s Act provides an intriguing and unique case study for the questions of ‘observe or intervene’, an example in which the filmmaker invites the subject to document his own memories and experiences in the Performative mode (Nichols, 2010: 199-211), while documenting the process and probing it’s outcomes in an Interactive mode, borrowing certain fly-on-the-wall elements of the Observational, without ever proposing to be an invisible eye following it’s protagonist like Cinema Verite (Hall, 1998: 223-237) or being dependant on the unstaged like Vertov’s “Film-Eye” (Petric, 1978: 30), and in the long standing tradition of Nanook of the North (1922) it adopts a central character to take a story across cultural borders with an ethnographic flavour, attempting largely to explore the point of view of the subject (Rony, 1996).

Reference:

Nichols, Bill. “Documentary Modes of Representation” [extract: Modes & The Expository Mode] Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 1991 p32-38

Hall, Jeanne. “Don’t You Ever Just Watch?”: American Cinema Verite and Don’t Look Back.” Documenting the Documentary. Ed. Barry Keith Grant & Jeannette Sloniowski. Detroit: Wayne State UP. 1998, 223-237

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary Film. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2010, pp.179-194 [Extract: The Participatory Mode, originally called the Interactive Mode]

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary Film. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2010, pp 195-199 [Extract: The Reflexive Mode.]

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary Film. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2010, pp. 199-211 [Extract: The Performative Mode.]

Jones, Kent. “I Walk the Line.” Film Comment, vol. 41:1, January-February 2005

Kaplan, E. Ann. “Theories and Strategies of the Feminist Documentary.” Millennium Film Journal, no.12, Fall 1982-83, 44-67.

Petric, Vlada. “Dziga Vertov as Theorist.” Cinema Journal 18:1 Fall 1978, pp29-44

Rony, Fatimah Tobing. “Taxidermy and Romantic Ethnography: Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North.” The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham, Duke University Press, 1996, 99-126

Corner, J. “A Fiction (Un)like Any Other?” Critical Studies in Television: Scholarly Studies in Small Screen Fictions, vol. 1, no. 1 (Spring 2006) pp. 89-96

Anderson, Benedict (1992), ‘Introduction’ and ‘Cultural Roots’ in Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London, Verso, pp. 5-7, 22-28, 33-36

Leith, D & Myerson, G. (1989) The Power of Adress: Explorations in Rhetoric, London, Routledge, [extracts] pp. xii-xv, 1-6, 79-88, 151-154, 177-179

Edward H. Spence, Andrew Alexandra, Aaron Quinn, and Anne Dunn, 2011. Media, Markets, and Morals. 1st Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

Aufderheide, P., Jaszi, P. and Chandra, M. (2009). Honest Truths: Documentary Filmmakers on Ethical Challenges in Their Work. American University School of Communication: Centre for Social Media.