Blog post #3 – Reflection

My television viewing practises have changed significantly over the past few years – through my childhood and early adolescence, the primary source of my viewing would be traditional television viewing, whether that be Foxtel or free – to – air T.V. This would typically take place within a communal space like the living room. However, nowadays my viewing practises lie primarily outside of the realm of traditional television. In terms of watching the actual television as opposed to online streaming services like Netflix, I rarely ever do so on my own. Any free – to air or Foxtel I watch is typically if someone in my family already has the T.V on, and it’s something like the news or ‘The Project’. Despite the primacy of Netflix and torrenting in my viewing habits, I do find myself still attached to the communal, familial viewing experience.

Silverstone argues that “patterns of media consumption – especially television viewing – are generated within these social, spatial and temporal relations” of the family and domestic spaces. (2003, p. 33) I also engage in communal viewing of Netflix, watching shows on the streaming platform like ‘Friday Night Lights’ on a weekly basis with family. The draw of shared viewing practises still holds, especially when my tastes in television align with others.

Admittedly, over the last few months I have been watching both ‘The Bachelor’ and ‘The Bachelorette’, and while I’m definitely drawn to the melodrama, I find that the appeal is mostly due to the communal experience which comes with it’s viewing. It’s a show that I’ll likely tweet about while viewing, as I find there is a particular pull into the appeal of “hate – watching” this programme alongside others virtually. It seems that social TV and use of the second screen is what is sustaining traditional television’s prominence in a media saturated society.

Consider the following article detailing ‘The Bachelorette’ finales’ high ratings and prominence on social media.

We’re so happy for Sam and Sasha! #BacheloretteAU pic.twitter.com/MrEoeJ0wIN

— #BacheloretteAU (@BacheloretteAU) October 22, 2015

The Bachelorette Australia’s twitter page engages fans via the second screen.

In week two of the course, scheduling and control was discussed, and how the organisation of scheduled programming dictates behaviours in domestic spaces. Lotz discusses how television as a medium “has been very much defined by its scheduele and particular patterns of use that developed in response.” (2009, p. 17) One of these patterns developed is gendered scheudeling. Traditionally, day time programming was associated with “female” programmes like soap operas. In the case of ‘The Bachelor(ette)’ I think we can see how gender scheduling has transformed to accommodate for working and studying women (and men) as these shows air on weekday evenings. However we can still recognise the how television exists as a planned structure to an extent still continuing to dictate daily life.

However, my viewing habits also distance themselves from traditional modes of scheduling and the planned flow. I watch shows which could be deemed as “complex narratives” and I find that to fully engage with these texts, it necessitates that I’m paying attention. As Sconce discusses, “US television has devoted increasing attention in the past two decades to crafting and maintaining ever more complex narrative universes… that suggests new forms of audience engagement.” (2004, p. 95) As a result, my viewing habits to watch these shows – like ‘Twin Peaks’ and ‘House of Cards’ heavily rely upon platforms like Netflix where I can watch, re – watch and pause episodes, my mode of audience engagement becoming a more intensive one.

Despite this, there are also plenty of shows which don’t necessitate this level of attention that I watch on Netflix, including sitcoms like ‘How I Met Your Mother’. I find it crucial to be able to choose when and where I can watch television especially during the semester where my time – use diary was completed. Streaming platforms and torrenting allow this kind of freedom.

In conclusion, while my viewing habits over this semester do continue to reflect some elements of the traditional experience of television, I think this experience is also modernised in a sense by my use of the second screen. Additionally, I can recognise that complex narratives requires a close reading and may result in our culture moving away from scheduled television viewing with the rise of services such as Netflix.

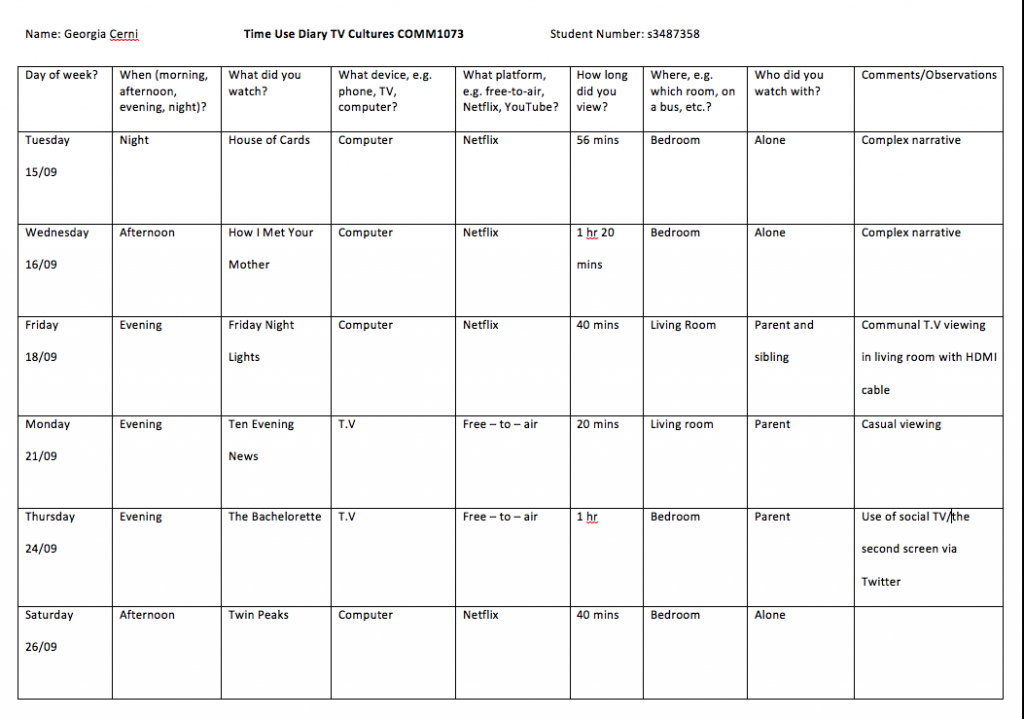

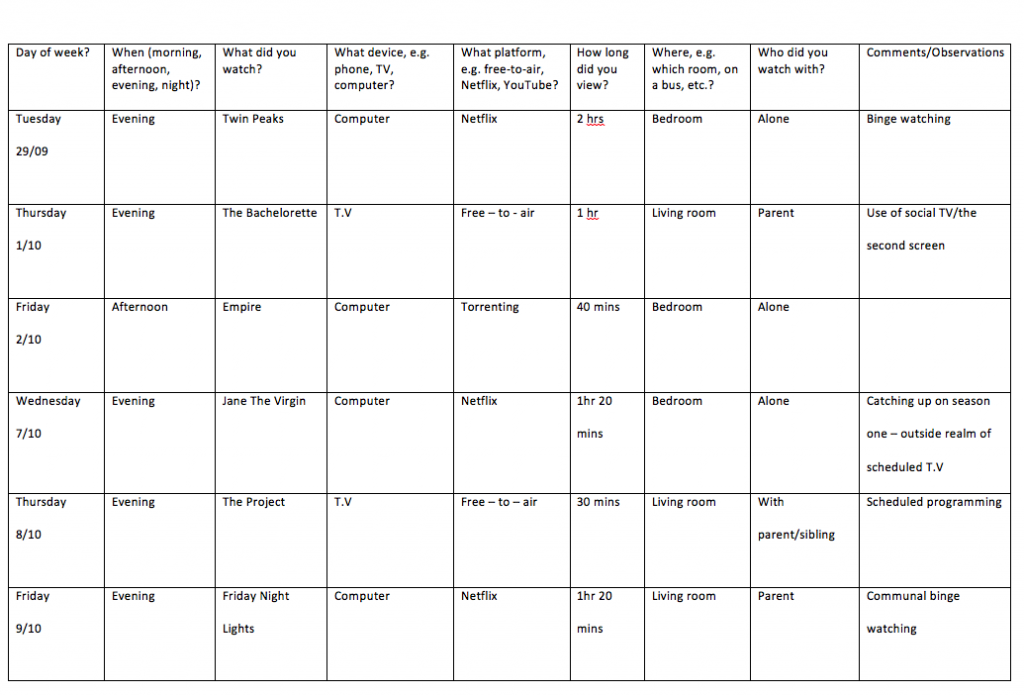

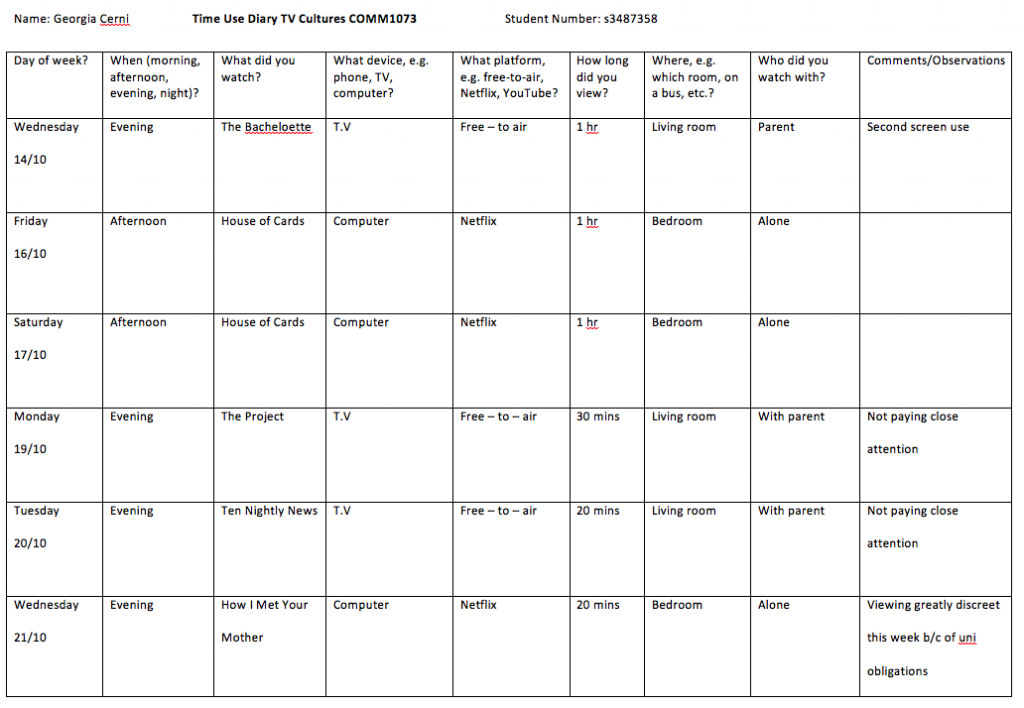

Time use diary – Week of 13th September – 23rd October

References

Adnews.com.au, (2015). Bachelorette tops ratings despite Daily Mail spoilers – AdNews. [online] Available at: http://www.adnews.com.au/news/bachelorette-tops-ratings-despite-daily-mail-spoilers [Accessed 27 Oct. 2015].

Lotz, A. (2009). Beyond prime time. 1st ed. New York: Routledge, p.17. Available from: EBL [27 October 2015]

Lynn, S. and Jan, O. (2004). Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition. 1st ed. Durham: Duke University Press, p.95. Available from: Google eBooks. [26 October 2015]

Silverstone, R 2003, Television And Everyday Life, London: Routledge, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost [27 October 2015.]