This morning I presented my Precursor assessment to the Writing as Researchers lab, in which we were to take a “slice” of our research question and interrogate it with regard to one of the lab’s themes (praxis | risk | resistance | obligation | ethics).

I decided to explore the character archetype of the Bloke through the lens of political resistance and national identity.

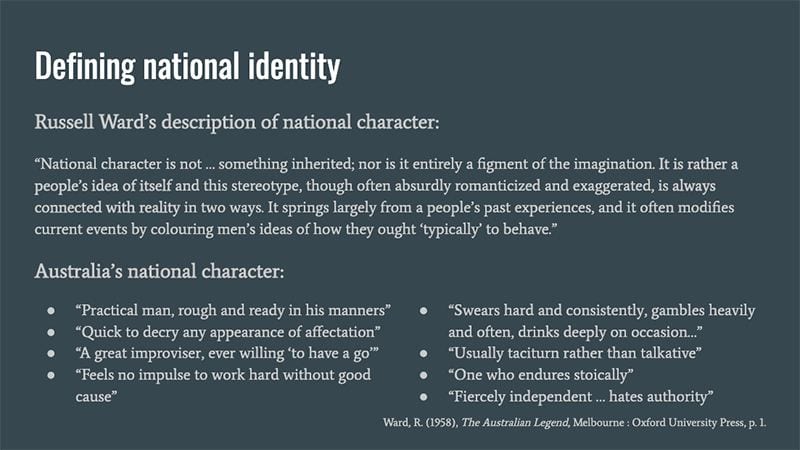

Much of Australia’s national identity — or “national character” as Russell Ward called it in his influential 1958 account — corresponds to the Bloke archetype, and is defined in terms of its resistance to the social norms of the city-dweller.

Ward posits that the Australian national character was forged by two things: our convict past (which accounts for the swearing, independence and suspicion of authority) and the landscape (which accounts for the physical toughness, as well as a pervasive insecurity that has been explored in media throughout our history).

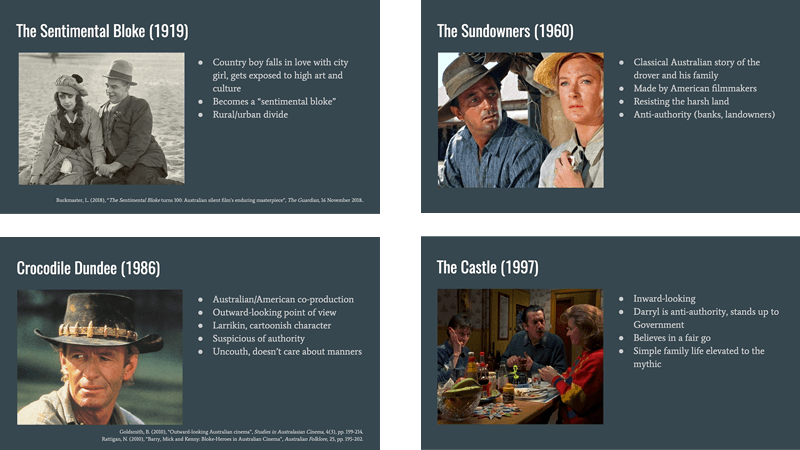

The Bloke has been portrayed in cinema for at least 100 years, going back to Raymond Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke (1919). Filmmakers have explored the various dimensions, expressions and limitations of the character in the time since, but resistance has remained a consistently important attribute.

One Night the Moon (2001, directed by Indigenous woman filmmaker Rachel Perkins) is a particularly interesting example as it both deeply critiques the character archetype while also giving a pretty classical, accurate portrayal. Perkins explores the negative side of the resistance that is usually cast as a positive.

Zooming out, much of Australian cinema (and, even further out, Australian culture at large) is defined by its resistance — to the British empire, to American cultural influence.

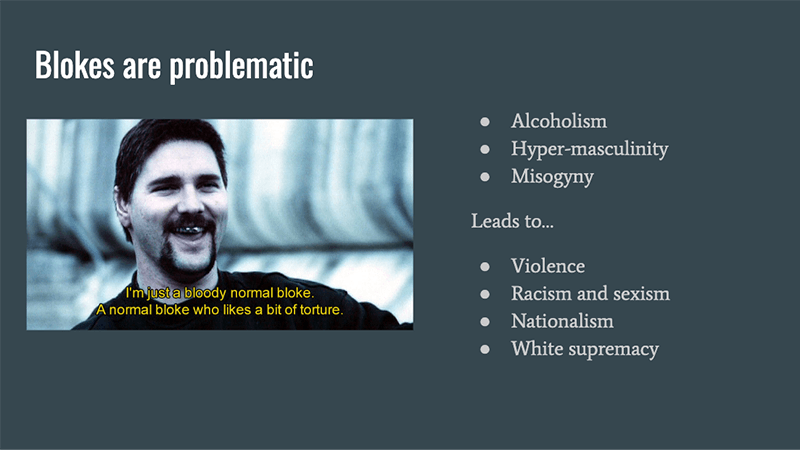

But there are some very obvious problems with the Bloke archetype as the standard expression of Australian national identity — namely, that it is a very narrow, specific character that increasingly doesn’t actually exist in society in great numbers.

And the Bloke archetype itself has so many inherently negative attributes associated with it that it could be argued that it bears some small responsibility for current social and political problems.

Although this exercise was a bit of a distraction from my main research topic, resistance seems to be central to much of Australia’s national identity (and therefore much of Australian cinema), so it’s something I will need to continue researching.