Analysis

In their essay ‘Web 2.0 Storytelling Emergence of a New Genre’, Alexander & Levine illustrate the primary issue affecting research into new digital technologies in that ‘trying to pin down such a moving target can result in creating terminology that becomes obsolete in short order’ (2008, p. 46). However, by basing their analysis of social media as a whole as representative of Web 2.0 technologies, Alexander & Levine (2008) create a useful framework in which to support their thesis and it’s under these tenants in which we’ll be evaluating our data.

In their essay ‘Web 2.0 Storytelling Emergence of a New Genre’, Alexander & Levine illustrate the primary issue affecting research into new digital technologies in that ‘trying to pin down such a moving target can result in creating terminology that becomes obsolete in short order’ (2008, p. 46). However, by basing their analysis of social media as a whole as representative of Web 2.0 technologies, Alexander & Levine (2008) create a useful framework in which to support their thesis and it’s under these tenants in which we’ll be evaluating our data.

Operating within this framework, Snapchat shares the fundamental aspects that define Web 2.0 technologies: microcontent, social software, and findability. Snapchat is made up of ‘snaps’ which constitute either video or image and both are small chunks of content which are formed to make a whole. Social software are ‘platforms that are often structured to be organized around people rather than the traditional computer hierarchies of directory trees’ (Alexander & Levine, 2008, p. 42) and typically contain content that has been ‘touched by multiple people’ (Alexander & Levin, 2008, p. 42). This is an important point to consider in regards to other research into social media. Luchman, Bergstrom, and Krulikowski define social media as ‘internet communication where more than one user can publish or post information within a community of users’ (2014, p. 137) and it appears that Snapchat’s relatively isolated creative process which limits other users imposing upon individual snap creations outside of responding to them is in breach of this definition. Finally, findability as it relates to Web 2.0, refers to tools like tags, geolocation, etc that allow users to find other users who may be producing similar microcontent through numerous means (Alexander & Levine, 2008). Where Snapchat differs to all of the above is that while it emphasises sharing and interacting with other users, users can only interact with people who use Snapchat and know each other’s account names. Furthermore, snaps cannot be shared outside of Snapchat and are thus limited in interacting with other social media and forming a larger tapestry of multiple media. These are only some of the contradictions our research has found in regards to social media and how it relates to Snapchat.

Our first question was used to determine the length of time our participants had been using Snapchat. The biggest result was two years for the majority of users while many other users simply had no idea when they first started using the app. The amount of participants that had only recently started using Snapchat for around 2-3 months was significant and, as such, we created a different category to accommodate them, suggesting that Snapchat, as of 2015 when we conducted this survey, is still attracting a consumer base and is in a healthy state. Finally, there were only a few users who had been using the app for three years and were the minority in our results; early adopters of the app a year after it first launched.

Our first question was used to determine the length of time our participants had been using Snapchat. The biggest result was two years for the majority of users while many other users simply had no idea when they first started using the app. The amount of participants that had only recently started using Snapchat for around 2-3 months was significant and, as such, we created a different category to accommodate them, suggesting that Snapchat, as of 2015 when we conducted this survey, is still attracting a consumer base and is in a healthy state. Finally, there were only a few users who had been using the app for three years and were the minority in our results; early adopters of the app a year after it first launched.

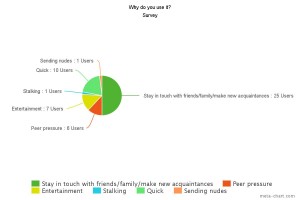

Our second question was designed to track usage results and, as we can see, the majority of users appreciate Snapchat as a way in which stay in touch with friends, family, and even make new acquaintances. Such an overwhelming result in this category supports Van House, Davis et al (2004) in their contention that one of personal photograph’s primary motivations of use is creating and maintaining social relationships. While Van House, Davis et al’s essay was produced in 2004 and was related to personal photography, Snapchat’s photo and video services share this heritage. Outside of the very specific, technological behaviour of sending photos from one user to another to be accessible on their mobile phone, the general behaviour of sharing photos from person to person can be readily understood within the same context of personal photography. Photos not only ‘reflect social relationships, but they also help to construct and maintain them’ (Van House, Davis et al, 2004, p. 7).

Our second question was designed to track usage results and, as we can see, the majority of users appreciate Snapchat as a way in which stay in touch with friends, family, and even make new acquaintances. Such an overwhelming result in this category supports Van House, Davis et al (2004) in their contention that one of personal photograph’s primary motivations of use is creating and maintaining social relationships. While Van House, Davis et al’s essay was produced in 2004 and was related to personal photography, Snapchat’s photo and video services share this heritage. Outside of the very specific, technological behaviour of sending photos from one user to another to be accessible on their mobile phone, the general behaviour of sharing photos from person to person can be readily understood within the same context of personal photography. Photos not only ‘reflect social relationships, but they also help to construct and maintain them’ (Van House, Davis et al, 2004, p. 7).

Outside of the majority of users who valued the ability to remain in contact with friends and family, the three following categories are more or less evenly matched in popularity: entertainment, peer pressure, and the notion of expediency (people enjoyed how simple and fast Snapchat is in allowing them to take photos or videos). It with this question, and these results, that our initial research question of how social media tells stories became difficult to apply to our data, as participants placed little value on this aspect of social media, instead preferring to use Snapchat to fulfill certain needs or motivations. Without further questions or surveys conducted, our results conclude either that participants already take storytelling as a given in what they produce with Snapchat, or instead prefer to use this app for other reasons. Brandtzaeg & Heim (2011) identify five types of users of social media as sporadics, lurkers, socialisers, debaters, and actives. Sporadics are ‘so named because they visit the community only from time to time, but not a frequent basis’ (2011, p. 41), lurkers are ‘low in participation’ and are ‘less likely to be contributors of user generated content’ (2011, p. 41), socialisers are characterised by their emphasis on communication between other users, debaters are ‘highly involved in discussions, readings, and writing contributions in general’ (2011, p. 42), and actives are ‘engaged in almost all participations activities within the community’ (2011, p. 42).

While not all of these user types are useful to us, some of these distinctions are helpful in analysing our data. While lurkers made up a significant portion of their audience for Brandtzaeg & Heim, only one user in our survey (under the category of ‘Stalking’) willingly identified themselves as such and placed importance on this attribute as the most important reason as to why they used Snapchat. Activities are difficult to measure in how they relate to our survey and could readily apply to any one of our results as we didn’t measure our participants level of engagement with Snapchat. Debaters are also difficult to measure in a similar way as their classification is contingent upon the level of discussion that takes place within communicating which, again, our survey does not take account of. Socialisers, however, constitute the majority of users of Snapchat by default as any type of interaction within the app involves communication with another user.

Perhaps a more useful classification of our results for this question, especially in regards to the third-largest category of ‘entertainment’, are the models developed by N. Luchman, J et al in their paper ‘A Motives Framework of Social Media Website use: A survey of young Americans’. N. Luchman, J et al develop several framework models to analysis their survey results and propose a fun-related dimension (2014, p. 138) which is ‘most strongly associated with fun, laughing, entertainment, and providing updates’ (2014, p. 138). Participants of our survey engaged with Snapchat and valued its ability to provide entertainment and, within the framework provided by N. Luchman, J et al, likely enjoy updating their experiences to other people within their network.

Our biggest question, in that it involved the most categories and generalisation, provides useful data in regards to our research question. The majority of users of Snapchat in our survey record things they find amusing to share with others, a result which falls neatly into the fun-related dimension framework provided by N. Luchman, J et al (2014). The emphasis placed on oneself’s was also highly valued in our survey and prescribes to Van House, Davis, et al’s social uses of photography being that of self-expression and self-presentation (2004). The emphasis of the individual in our survey, and the nature of Snapchat as a social media platform that encourages sharing, highlights the fact that Snapchat users ‘believe they have a story worth sharing’ (Vienne, S & Burgess, J, 2013, p. 286) and is demonstrative of a much larger trend in digital media today in which self-representation is of primary importance and people retain agency over their self-representation. Participants of our survey value the representation of themselves and enjoy sharing their point of view with their friends and associates.

Our biggest question, in that it involved the most categories and generalisation, provides useful data in regards to our research question. The majority of users of Snapchat in our survey record things they find amusing to share with others, a result which falls neatly into the fun-related dimension framework provided by N. Luchman, J et al (2014). The emphasis placed on oneself’s was also highly valued in our survey and prescribes to Van House, Davis, et al’s social uses of photography being that of self-expression and self-presentation (2004). The emphasis of the individual in our survey, and the nature of Snapchat as a social media platform that encourages sharing, highlights the fact that Snapchat users ‘believe they have a story worth sharing’ (Vienne, S & Burgess, J, 2013, p. 286) and is demonstrative of a much larger trend in digital media today in which self-representation is of primary importance and people retain agency over their self-representation. Participants of our survey value the representation of themselves and enjoy sharing their point of view with their friends and associates.

Examining this question within the framework of motivational usage behind social media, we can see that the user type of lurkers (Brandtzaeg & Heim, 2011) is once again represented, however minor, alongside the primary user type of socialisers, supporting the notion within our study that Snapchat users are predominantly active participants.

Participants of our survey primarily found that documenting and sharing individual, personal lives as the most distinct from traditional media, with the ephemeral nature of the medium (how snaps delete themselves after a certain amount of time) as a close second. The immediacy of the app was again highlighted as a positive alongside what we called a ‘lack of judgement’ referring to the fact that participants of our survey felt more at ease sharing things as they were going to be deleted after a certain period of time. The ephemeral nature of the medium and the lack of judgement are thus intertwined within the context of Snapchat as participants of our survey noted that it was because their snaps were going to deleted that they were capable of feeling less judged and more free to share whatever they wanted. This central idea of Snapchat (that snaps are deleted after a certain period of time) supports the notion by Van House, Davis, et al (2004) that photography constructs personal and group memory perhaps even more so than traditional photography allows as it deletes the very same artefacts (the photograph or video) that allow the memory to be formed. This stands in contrast to traditional photography which often enshrines the photograph as being the primary method in which to remember things by and is supported by behaviour in which ‘photos are often the one thing that people rush to save when their house burns’ (Van House, Davis, et al, 2004, p. 1). The process of deletion inherent to Snapchat paradoxically invites the possibility of forgetting and thus forms a complete picture of what constitutes memory. Finally, the process of deletion in Snapchat reinterprets personal photography as a dialogue between people rather than an artefact of past time which can be recalled, promoting Van House, Davis, et al’s (2004) assertion that personal photography is concerned with creating and maintaining social relationships above and beyond constructing personal and group memory and self expression and self presentation.

Participants of our survey primarily found that documenting and sharing individual, personal lives as the most distinct from traditional media, with the ephemeral nature of the medium (how snaps delete themselves after a certain amount of time) as a close second. The immediacy of the app was again highlighted as a positive alongside what we called a ‘lack of judgement’ referring to the fact that participants of our survey felt more at ease sharing things as they were going to be deleted after a certain period of time. The ephemeral nature of the medium and the lack of judgement are thus intertwined within the context of Snapchat as participants of our survey noted that it was because their snaps were going to deleted that they were capable of feeling less judged and more free to share whatever they wanted. This central idea of Snapchat (that snaps are deleted after a certain period of time) supports the notion by Van House, Davis, et al (2004) that photography constructs personal and group memory perhaps even more so than traditional photography allows as it deletes the very same artefacts (the photograph or video) that allow the memory to be formed. This stands in contrast to traditional photography which often enshrines the photograph as being the primary method in which to remember things by and is supported by behaviour in which ‘photos are often the one thing that people rush to save when their house burns’ (Van House, Davis, et al, 2004, p. 1). The process of deletion inherent to Snapchat paradoxically invites the possibility of forgetting and thus forms a complete picture of what constitutes memory. Finally, the process of deletion in Snapchat reinterprets personal photography as a dialogue between people rather than an artefact of past time which can be recalled, promoting Van House, Davis, et al’s (2004) assertion that personal photography is concerned with creating and maintaining social relationships above and beyond constructing personal and group memory and self expression and self presentation.

In our last question, participants of our survey overwhelmingly voted in support that they have experienced positive effects from using Snapchat. Others chose to expand upon this, stating that they have experienced a growth in friendship, laughter, spontaneity, and appreciated being able to stay in touch with people far away. With only 8 users out of 50 to respond in the negative, our survey data supports the fun-related dimension of social media usage (N. Luchman, J et al, 2014). The use of action words by our participants to describe their use of Snapchat on the whole suggests that they tend towards the user type of socialisers (Brandtzaeg & Heim, 2011) with a minimum of lurkers. The methods of interaction inherent to Snapchat on the whole promote a merging of the two user types of socialisers and actives as to be a socialiser in Snapchat is to produce content for others to share.

In our last question, participants of our survey overwhelmingly voted in support that they have experienced positive effects from using Snapchat. Others chose to expand upon this, stating that they have experienced a growth in friendship, laughter, spontaneity, and appreciated being able to stay in touch with people far away. With only 8 users out of 50 to respond in the negative, our survey data supports the fun-related dimension of social media usage (N. Luchman, J et al, 2014). The use of action words by our participants to describe their use of Snapchat on the whole suggests that they tend towards the user type of socialisers (Brandtzaeg & Heim, 2011) with a minimum of lurkers. The methods of interaction inherent to Snapchat on the whole promote a merging of the two user types of socialisers and actives as to be a socialiser in Snapchat is to produce content for others to share.